A caretaker of a Philippine historical site in the United States accused the Smithsonian Institution of lying about its repatriation commitment to Filipino remains.

Janna Añonuevo Langholz, the caretaker of the Philippine Village Historical Site from the St. Louis World Fair 1904, addressed Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch III in a public letter on Instagram on August 28.

In her letter, Langholz claimed that he and the institution lied to her about honoring the remains of the individuals who took part at the controversial world fair.

“Your institution lied to me about the actions you were taking to honor the remains of the individuals from the 1904 World’s Fair who still remain in the collections. Why should I trust that you are moving forward in this process with care and respect?” she wrote.

Langholz also said that she was rejecting Bunch’s apology letter, further saying that he had not apologized to her directly.

“Dear Smithsonian Lonnie Bunch of the Smithsonian Institution, I do not accept your apology. Your institution incinerated the remains of someone very important to me,” Langholz said.

“How can you expect forgiveness when you haven’t even yet apologized directly,” she added.

View this post on Instagram

Langholz was referring to the apology letter Bunch wrote to the Philippines. It was published in the Washington Post’s op-ed section on August 20.

This letter came after The Post released a report that exposed the Smithsonian’s staggering collection of bones and brains of individuals from different parts of the world.

The publication also unveiled the racial brain collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington, D.C. It was amassed by an anthropologist named Ales Hrdlicka, also called the “bone doctor.”

Such extensive findings prompted Bunch to issue a public apology to the world, especially to the countries whose remains of individuals were found.

“As secretary of the Smithsonian, I condemn these past actions and apologize for the pain caused by Hrdlicka and others at the institution who acted unethically in the name of science, regardless of the era in which their actions occurred,” Bunch said.

“I recognize, too, that the Smithsonian is responsible both for the original work of Hrdlicka and others who subscribed to his beliefs, and for the failure to return the remains he collected to descendant communities in the decades since,” he added.

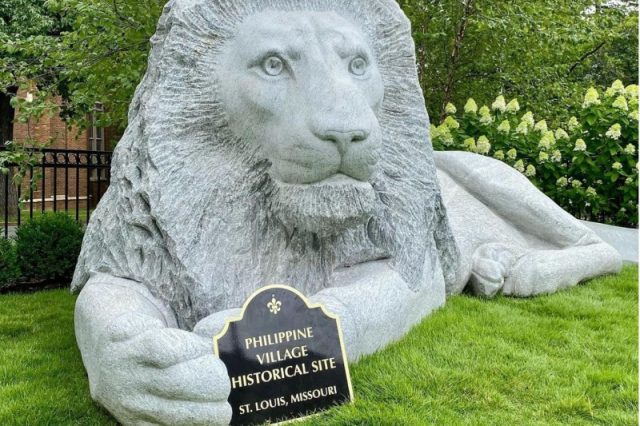

The Philippine Village Historical Site, meanwhile, serves as a living landmark in Clayton, Missouri to remember the inhumane conditions indigenous people experienced as part of the World’s Fair.

On Maura’s remains

Langholz, however, said that the Smithsonian cut off its contact with her in November 2022, thus leaving her in the dark about the state of the remains of a girl named Maura.

One of the unwilling participants of the 1904 World Fair, Maura’s story from the time she was recruited in the Philippines to her death in the United States was highlighted in a graphic novel titled “Searching for Maura.”

The graphic novel was also published by The Post.

READ: ‘Searching for Maura’: The Washington Post releases graphic novel about lost Filipino girl

“When the Smithsonian cut off contact with me in November 2022, I was forced to wait months in silence, in grief, in anger for what your institution did to Maura without sympathy or explanation,” Langholz claimed.

She also asserted: “Your institution promised me for years that I would be welcomed in Washington, D.C. to pay respects to Maura. Now, there is nothing. You cannot make a young woman disappear without consequences.”

“How could you do this to me? How could you do this to us?” Langholz said.

To end her letter, Langholz said she will not accept Bunch’s apology she has seen the Smithsonian’s efforts to honor the remains.

“Your institution has stolen the voices of thousands, but you cannot silence mine,” Langholz said.

The National Museum of the Philippines has previously welcomed the Smithsonian’s initiative to bring home the remains of Maura and those of other Filipinos.

According to The Post’s report, the United States museum accumulated more than 30,000 human bones and other parts, including more than 200 brains.

READ: US museum eyes to repatriate Filipinos’ remains from racial brain collection