- ‘Digital authoritarianism’ seen rising in Southeast Asia

- Independent news outlets, journalists targeted

- Rights groups fight back by boosting cybersecurity savvy

MANILA (Thomson Reuters Foundation) — When hackers targeted independent Filipino news outlet Bulatlat.com, flooding its website with a torrent of rogue traffic, staff had to rely on digital forensics experts in Sweden to track down the perpetrators.

“Building the case means you must come up with evidence. But digital forensics is something we simply don’t have any resources for,” said Frank Lloyd Tiongson of the National Union of People’s Lawyers, which represented Bulatlat over the 2018 attack.

Whether targeting ordinary people, journalists or activists, online threats from doxxing to domain blocking and digital surveillance are rising in the Philippines and other Southeast Asian nations, highlighting a lack of resources and expertise to fight them, experts say.

Governments are often behind such online threats in nations including Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar and the Philippines, said Bangkok-based digital rights group, DigitalReach, a global phenomenon dubbed digital authoritarianism.

“It’s become a trend in Southeast Asia when a repressive government knows how important the digital space is for civil society and thinks it’s part of the state’s job to control it,” Sutawan Chanprasert, DigitalReach’s founder, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Last month, two Thai activists sued the government for allegedly using Pegasus spyware to monitor their mobile devices.

The hacking on Bulatlat five years ago, which the newspaper says was “targeted, deliberate and well-organized”, was the first known distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack against a Filipino media organization.

Hackers involved in DDoS attacks direct high volumes of internet traffic towards targeted servers in a relatively unsophisticated bid to knock them offline.

Lacking the technical expertise to track down the hackers and respond to the attack, senior staff at Bulatlat called a digital security helpline operated by Access Now, an international digital rights advocacy group.

Access Now put them in touch with Sweden-based Qurium Media Foundation, where digital forensics specialists were able to trace the intrusion to two Philippines-based IT companies.

The companies, which were also linked to DDoS attacks on three other independent news websites in the Philippines, agreed a financial settlement in the civil case brought against them.

How can hackers be stopped?

For digital rights activists, however, the case was a relatively rare success story of holding hackers to account.

The Philippines ranks second — after Mongolia — among countries most plagued by web threats worldwide, according to a 2022 report global cybersecurity company Kaspersky.

But there are only 300 practicing cybersecurity experts in the country, which would ideally count on 200,000, according to the Department of Information and Communications Technology.

With 85 million internet users, or more than 70% of the population, the country should invest more in cybersecurity measures and make the issue a key priority, said a 2022 report by The Asia Foundation, a nonprofit.

Growing concern about online threats has prompted civil society groups in the region to look for new ways to respond themselves.

Some are offering digital security training for individuals at risk on safeguards such as digital encryption, virtual private networks (VPNs) and safe applications.

But Sutawan said that while digital security training works on the individual level, Southeast Asia needs to adopt a more collective approach.

This includes having local focal points that are trusted by dissidents with whom they can share their experience in their own local languages and conducting more technical research to analyze the threats in each country.

Stronger cross-border cooperation, as in the Bulatlat case, is also seen as vital for preserving internet freedom.

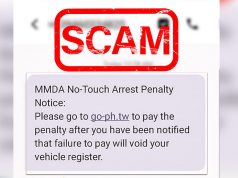

While there are “very palpable digital security threats” against journalists and activists, Marlon Nombrado of digital rights group Out of the Box said ordinary citizens are also affected, for example in the form of phishing scams, doxxing or personal data misuse.

Last January, his group trained 20 women in a poor urban community in Manila on digital rights and internet security, including how to prevent and respond to so-called doxxing — the malicious posting of personal information on social media.

While different to the digital authoritarianism that targets dissenting voices and journalists, Nombrado said fighting online abuse in all segments of society was about protecting basic rights and freedoms.

“Because the media landscape is evolving, issues of digital security and safety cannot be separated from human rights,” he said.

— Reporting by Mariejo Ramos. Editing by Helen Popper. The Thomson Reuters Foundation is the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters. Visit https://www.context.news