A Facebook page that supports the usage of “Pilipinx” accused the Ati-Atihan Festival, which was considered as a national cultural heritage, as cultural appropriation due to the supposed blackface of performers.

The terms “Pilipinx” and “Filipinx” were used by some Filipinos overseas to supposedly refer to a gender-neutral description of their identities.

In a post on October 31, Facebook page called “Pilipiinx against Colonialism” alleged the age-old practice of darkening the skin of Ati-Atihan performers during the event as a mockery to Africans despite it being a commemorative ritual of the natives in the province of Aklan.

The post also suggested that the group was only made aware of the festival’s activities despite it being celebrated since 1871.

“Mga Kababayan, it was recently brought up to us that the Mainlanders practice an oppressive cultural practice called the Ati-Atihan. It is a festival where people dress up in colorful (non-native clothes) and in alarming amounts of Blackface,” the post read.

“While we understand that the mainland Filipinx are outdated socio-politically particularly with updated norms in the West and America, we advocate for social reformation. Stop culturally appropriating Africans, stop blackfacing,” it added.

In the page’s profile, they described themselves as:

“Pilipinx para sa mga katutubo. We stand for Equal rights for the Oppressed. Color and Gender discrimination are evil. Resist self-colonization, Pinxys. #BLM #FilipinxBLM #PilipinxBLM #Feminism #LGBTQIA.”

The religious festival and blackface

By definition, blackface is “dark makeup worn (as by a performer in a minstrel show) in a caricature of the appearance of a black person.”

Its origin dates back to the mid-19th century when white performers paint themselves black to mock enslaved dark-skinned Africans.

However, while similar in gesture, performers of the Ati-Atihan Festival wear black soot to pretend to as Atis, dark-skinned indigenous peoples, who historians believed to be the first inhabitants of the Philippines. The celebration also honors the Sto. Niño or the Child Jesus.

The name itself “Ati-Atihan” translates to “making like Atis” or to to pretend to be like the aboriginal natives of Aklan, the Atis. It is celebrated every 3rd Sunday of January.

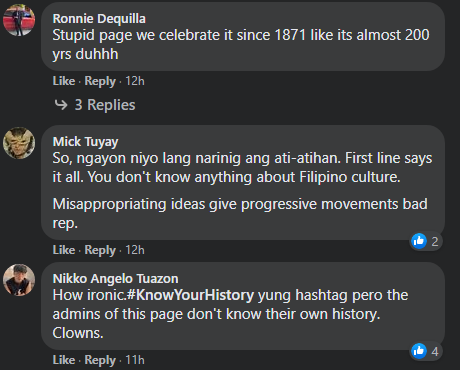

This was pointed out in the comments section of the page’s post where some noted the harm that the false information the page’s administrators are perpetuating.

A lecturer on Twitter with the handle @janwriter_, meanwhile, described the idea being put forth in the post as a form of “cultural colonialism.”

“This is cultural colonialism. The world doesn’t revolve around America. Filipino-Americans should leave native Filipino traditions alone,” he said.

This is cultural colonialism. The world doesn’t revolve around America. Filipino-Americans should leave native Filipino traditions alone.

Also, ‘nuff of this “filipinx” bullshit. pic.twitter.com/YGbvE2aZAB

— Jan Writer (@janwriter_) November 3, 2020

‘The Mother of Philippine Festivals’

The National Commission for Culture and the Philippines named the Ati-Atihan Festival in Kalibo, Aklan as the “The Mother of Philippine Festivals” because it inspired other popular festivals in the country such as the Dinagyang Festival of Iloilo and the Sinulog Festival in Cebu.

There are two stories surrounding its origins. The popular and the NCCA-recognized story follows the fisherman’s discovery of a wood-carving of Child Jesus while fishing during the early 1700s.

The fisherman initially placed it at an altar. From then on, the family received good fish harvests and other blessings.

The priest later advised them to place it at the Ibajay Parish in Aklan. However, residents still managed to find the wood at the roof of the fisherman’s house.

When a group of Spaniards known as “Moros” tried to invade the town, the residents fought back and won. They attributed their success to the presence of the wooden relic.

This historic battle was commemorated during the Ati-Atihan celebrations wherein performers paint black soot to depict the early natives.

Another story, which the NCCA stated was a myth, follows the arrival of 10 Bornean datus or chieftains to Aklan where the native Aetas welcomed them.

The Bornean leaders then bought the entire Panay Island, where Aklan is located, from them with gold jewelry.

The festival was officially established on June 11, 1871.