A lawmaker claimed that there were no starving children in the past due to the presence of Nutribun, which was actually produced to combat the country’s malnutrition problem in the 70s.

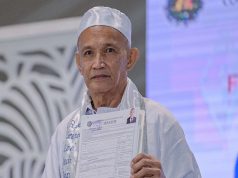

Sen. Imee Marcos on June 4 went to Davao City to thank Filipinos who supported her brother, president-elect Ferdinand Marcos Jr, in the 2022 elections.

In her address, she mentioned the vitamin-enriched bread which has been falsely attributed to the Marcoses, especially during the reign of their father, late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr.

“Nutribun! Walang nagugutom na bata noon, kay Nutribun ang sagana,” Imee exclaimed.

“Kapag kakainin mo, parang semento sa tiyan, may kasama pang tagaktak ng Klim (na) gatas. Ang mga lolas and mommies talagang fully charged hanggang ngayon dahil powered by Nutribun!” she added.

RELATED: Spotted: ‘Nutribun’ distributed to Cebuanos branded with Imee Marcos’ name

Her comments didn’t amuse some Filipinos on Facebook who pointed out the context and history behind the famous bread.

“Maraming gutom noon. In fact, kaya naglabas ang ayuda ang USAID para labanan ang malnutrisyon… tinitimbang mga bata noon.. ‘pag pumasok sa category ng underweight, kasama siya sa subsidy ng Nutribun at gatas…. ‘pag ‘yung nasa tamang timbang, ibenebenta ito sa kanila,” a Facebok user wrote.

“Kaya nga may Nutribun kasi nakita USAID na malnourished ang mga bata. Kaya mo ‘yan Imee HAHAHA,” another online user said.

“Kaya nga nagka-Nutriban kasi madaming malnourished na mga Filipino (epspecially) mga bata… Kaya nga may ayuda from USAID to uplift hunger in the Philippines… Madam, ‘wag naman i-revise ang history,” wrote a different Facebook user.

Nutribun and malnutrition

The Nutribun was a product of the United States Agency for International Development‘s (USAID) mission in the country during the late 1960s.

It was introduced as a supplement in feeding programs to combat malnutrition among elementary students and serve food during emergencies like nature-related disasters and calamities.

USAID formulated it as a “ready-to-eat complete meal” while its Food For Peace program and Cooperation for American Relief Everywhere (CARE) donated ingredients.

The local commercial bakeries produced and delivered the goods to schools.

The bread became associated with the Marcoses after former first lady Imelda Marcos stamped its bags with her name and claimed it was part of her “Tulungan Project.”

While Imelda thought of the project, it was done in coordination between the USAID and the Department of Social Welfare. The project also coincided with the arrival of Nutribuns.

In a report presented to the Philippine Catholic Relief Services in 1973, the head of Biochemistry and Nutrition at the Virginia Polytechnic University said that USAID “had an interest in the malnutrition problem in the Philippines for many years.”

There have been initiatives from the United States as early as 1957, according to the report.

By 1967, late health secretary Paulino Garcia of the Marcos Sr. administration “recognized that the malnutrition problem in the population was of paramount importance particularly among infants and preschool children.”

“Within a few months after this conference, the USAID mission responded to a request from the Philippine Government to lend technical advisory services for the planning of a National Nutrition Program,” the report said.

A central part of the government’s nutrition scheme was done in schools and its target was to feed 2.7 million underweight or malnourished children, particularly in public elementary schools.

This was not achieved, according to fact-checking site VERA Files.

The AID reported that from 1971 to 1982, the maximum achieved was having fed 1.7 million children in 1973. By 1982, it stalled to 1.25 million children.

There was also the case of malnourished children on the Negros island.

A 1986 report from the Washington Post cited that 74% of children below 15 in the Negros Occidental province were “estimated to be suffering from varying degrees of malnutrition.”

Famine in Negros

In the 1980s, Negros suffered famine. Part of this was due to the decline of its sugar industry as countries outside the Philippines became more self-sufficient with their production.

Another part was due to the crony of Marcos Sr.

Roberto Benedicto, the appointed head of the National Sugar Trading Corporation, passed the losses to sugar planters when the markets fell.

They were left with $400 million in debts and additional interest rates.

“Through it all, the worst hit have been the hacienda workers, most of whom were paid well below the minimum farm wage even in good times and lived at or below the poverty line,” the Washington Post report reads.