- Junior doctors to walk out for 72-hours over pay

- Burnout and conditions driving junior doctors to quit

- Britain’s health service has record backlogs

- Junior doctors saddled with student debt

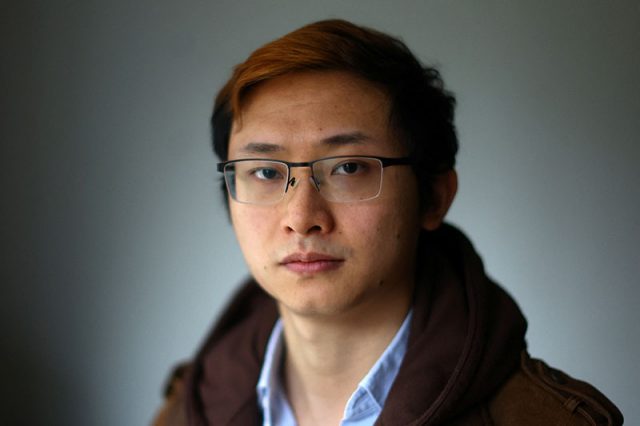

LONDON — Fed up with a government he says doesn’t care, Poh Wang plans to go on strike with tens of thousands of other British junior doctors next week, saying he is overworked, underpaid and burdened with a student loan he cannot imagine paying off.

The 28-year-old says he and his colleagues have been pushed to the brink after below-inflation pay rises collided with the surging cost of living to leave him questioning how he can ever pay off his more than 85,000 pounds ($101,000) of student debt.

On top of that, he remains incensed at his treatment during the pandemic, when he felt powerless to cope with the onslaught of patients arriving in hospital with COVID-19 symptoms — saying public displays of support did not pay the bills.

He joins junior doctors across England who will go on strike on March 13 for three days, protesting over pay and burnout that risks driving staff out of the health service as it tackles record-high patient waiting lists.

“We’ve reached a boiling point where we have had enough,” said Wang — a council member of the British Medical Association (BMA), which represents doctors and medical students.

“The anger is palpable that we have been used and abused and devalued to this extent.”

The son of Chinese immigrants who ran a takeaway restaurant in Chester, northern England, Wang became a doctor because he enjoyed helping people. Having attended medical school for six years, he has worked for five, two in specialty training as a psychiatry doctor.

Junior doctors are qualified physicians, often with several years of experience, who work under the guidance of senior doctors and represent a large part of the country’s medical community.

He is paid around 40,000 pounds a year for his base 40 hours a week, and works additional hours which can add up to around 48 hours a week. He rents a room in a shared flat in west London, an option that can cost around 1,000 pounds a month.

‘Above and beyond’

Early on in the pandemic, Wang worked as an emergency medicine doctor in south London where he and colleagues had to make difficult decisions, and comfort those patients who could not be admitted into intensive care units because they were full.

“We went above and beyond to do everything that we could,” he said.

He said the fact that he is struggling to get by financially now, as food inflation hits 17% in Britain, leaves him and his colleagues increasingly bitter about the last few years.

“We hate the sound of clapping, applause, because it’s empty,” said Wang, referring to Britain’s Clap for Our Carers campaign for health workers during the height of the pandemic.

“If you value us and what we’ve gone through and in terms of the sacrifices that we’ve made then pay us properly.”

The BMA says junior doctors’ take-home pay has been cut by more than a quarter over the last 15 years, when using the Retail Price Index (RPI) gauge of inflation.

It says its members voted overwhelmingly to strike.

The walkouts by junior doctors will put more pressure on the state-funded National Health Service (NHS) which is experiencing waves of strike action by nurses, ambulance workers and other staff.

Daniel Zahedi, 27, is another junior doctor who plans to go on strike on Monday. He describes his hospital in Cambridge, eastern England, as chronically understaffed and struggling.

“A lot of the time there’s not enough of us,” Zahedi said.

As a first-year doctor after his medical degree, Zahedi said he gets around £29,000 per year as base pay for 40 hours a week minimum. He said he worked roughly 60 hours this week, which was a bit above the average but “not unusual”. His student loan debt stands at around 100,000 pounds.

“It’s not just 100 grand as a student, you’ve got to pay to be a member of your Royal College, you pay to do exams, to even progress in your career,” he said.

Zahedi said, as things stand, he cannot see himself remaining in the profession in the long term, despite his love for the job.

“People are burning out left, right and center — where pay is just getting eroded year after year, where conditions are getting worse, where patient care is being damaged,” he said.

“They are feeling undervalued and people are leaving.”

In January, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak outlined the need to cut hospital waiting times as one of his government’s five priorities.

Battling strikes across multiple sectors including train drivers and teachers, the government has said public sector pay restraint is needed in order to get double-digit inflation under control.

($1 = 0.8389 pounds)

— Writing by Farouq Suleiman; Editing by Kate Holton and Janet Lawrence