A book about the Philippine economy co-written by the coming socio-economic planning secretary debunked the still-prevalent claim that the Marcos regime was a “golden era” for the Philippines.

The book titled “The Philippine Economy: Development, Policies, and Challenges” was published by the Oxford University Press in 2003.

Arsenio Balisacan, the impending appointed secretary of the National Economic and Development Authority, co-edited this book. He was also on the list of contributors.

Balisacan’s co-editor is a Hal Hill, a professor of Southeast Asian Economies at the Australian National University at the time the book was published.

The golden era myth, meanwhile, has been floated around for decades since the revolution ousted dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. from power.

This myth was largely supported by stories on instilled discipline among Filipinos, high wages for workers, free-flowing traffic and other supposed economic privileges during Marcos’s presidency.

Supporters of the Marcos family were mostly the ones parroting the possible return of such an era.

Fact-checkers, however, have since disputed and debunked these narratives with economic data and other relevant information from experts.

RELATED: Tiktoker’s quickfire recap of Philippine 70s-80s economy is a must-see

The Philippine economy book that Balisacan contributed to is among the references that showed a clearer picture of why the “golden age” is a false and simplistic belief.

Joshua Agar, a wind engineer and professor at the University of the Philippines, shared a digital copy of the book on Twitter on May 28.

“The incoming NEDA secretary writing in his book that the Marcos dictatorship was not the golden era,” Agar said.

The incoming NEDA secretary writing in his book that the Marcos dictatorship was not the golden era.

E-copy of the book:https://t.co/NZV9DHi4u5 pic.twitter.com/9tWoO9YlSX

— Joshua C. Agar (@JoshuaCAgar) May 28, 2022

The book’s abstract on Oxford’s website describes the Philippines as “one of the world’s development puzzles.”

It reads:

“Despite having many of the same conditions for successful economic growth as its neighboring East Asian countries, the country missed out almost completely on the Asian boom and never became one of the ‘Asian tiger’ economies.”

The full picture

In chapter 1 titled “An Introduction to the Key Issues”, Balisacan and Hill provide data and graphs on the growth rates of the country since the 1970s, which was the decade Marcos placed the country under Martial Law.

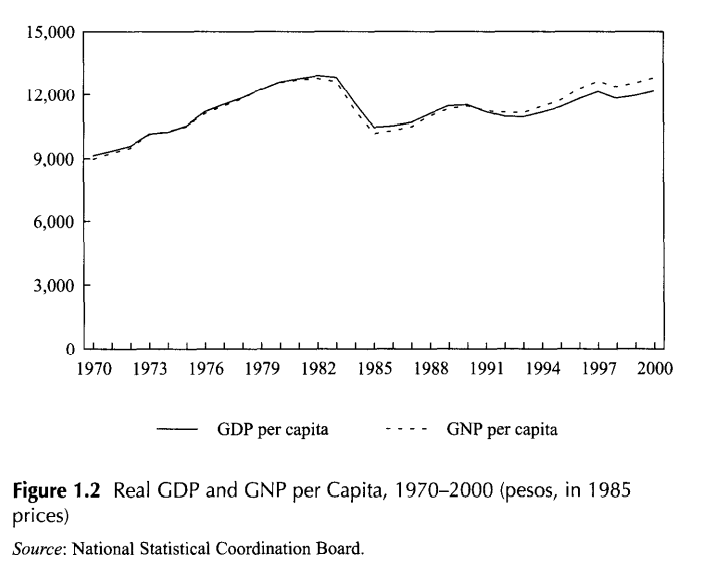

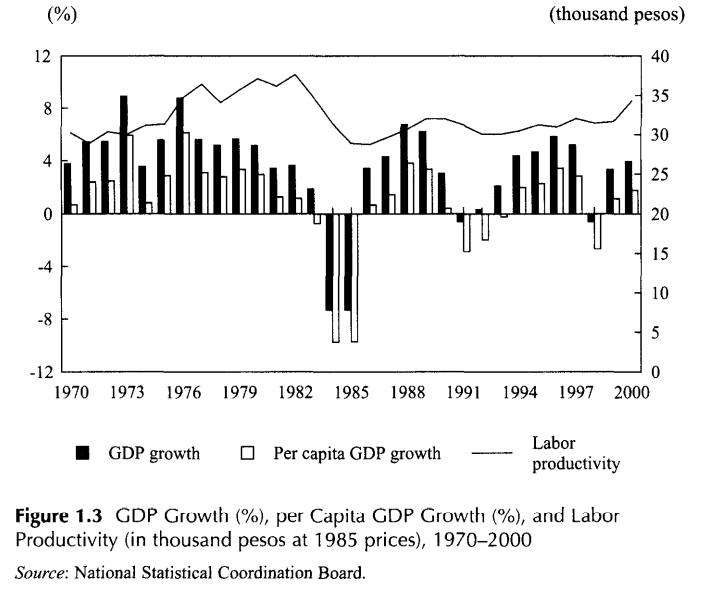

In figures 1.2 and 1.3 of the book, the graphs showed that the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) skyrocketed before collapsing in the 1980s.

Balisacan and Hill explain that the 1970s was a “decade of continuous expansion” with an average GDP growth rate of 5.8% annually. However, this was not sustained in the long run.

“The 1970s were a decade of continuous expansion, with GDP growth averaging 5.8% annually. In every year during that decade, growth in both GDP and per capita GDP was positive, with peaks in excess of 8% GDP growth twice, in 1974 and 1977. However, by the late 1970s growth was more subdued, at less than 6%,” they write.

“It then collapsed in 1984, as a political and an economic crisis set in,” they continue.

The assassination of former senator and opposition leader Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. was cited as a trigger for the economic collapse.

Dean Ronald Mendoza, meanwhile, said that this tragic event exposed “what was already a simmering political and economic crisis.”

READ: Debt, deprivation and spoils of dictatorship | 31 years of amnesia

Unsustained growth: A ‘debt-driven’ era

The experts explained that the country’s economy from 1970 to 1983 was actually “debt-driven.”

Their explanation reads:

“It was driven by large overseas borrowings. This strategy was unsustainable since the funds were generally not invested productively, and by the early 1980s the country had essentially hit its borrowing limits.”

Political turmoil then played a huge role in the deep crisis from 1984 to 1986, according to their assessment.

Part of it reads:

“Political and economic events together resulted in a very large economic contraction, the largest in the country’s post-independence history. President Marcos was finally removed from office in February 1986, through a combination of disputed electoral returns and massive demonstrations along Manila’s main arterial route, EDSA.”