TBILISI/BANGKOK(Thomson Reuters Foundation)— From the Philippines to Italy, homeless people have faced fines or arrest for failing to comply with coronavirus lockdown restrictions, activists and researchers warned, calling for more support and leniency from authorities.

Governments around the world have been racing to house the estimated 1.8 billion people who are homeless or live in inadequate housing and are uniquely at risk of being infected and infecting others during the pandemic.

But housing campaigners said many of the measures taken – from opening up shelters to making more funds available to homeless charities – fall short and are accompanied by counter-productive, strict policing and enforcement.

Leilani Farha, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, said she had been “appalled” to hear that in countries like France and Nigeria people had been ticketed, arrested, and “treated as criminals”.

“This is state behaviour against homeless people that we certainly saw pre pandemic … But in the time of COVID-19 it can be a death sentence,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in emailed comments.

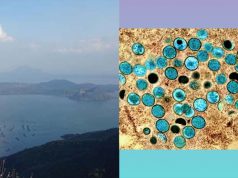

Worldwide, at least 2.6 million people have been reported to have been infected by the respiratory disease and about 185,000 have died, according to a Reuters tally.

Health experts say the homeless are more likely to contract illnesses such as the coronavirus, in part because of weakened immune systems due to additional stress, and lack of nutrition and sleep..

They also often suffer underlying medical conditions that make an illness more serious when it does break out.

Priya Kale, a woman living in a homeless shelter in northeast Delhi with her husband and five children, said a doctor had yet to visit the shelter of nearly 100 families.

“If someone falls sick here, it would be very hard, because it is a small place, and there is no room to keep distance,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Fines and arrests In the Philippines, where President Rodrigo Duterte warned that anyone violating lockdown measures could be shot, tens of thousands of people have been arrested for breaking curfew or disobeying authorities, according to human rights groups.

Many among them were homeless people. At the same time, homeless shelters in Manila have been shut for violating quarantine conditions, forcing millions of people to seek shelter in empty churches and schools.

“Many of those violating the lockdown measures are doing so out of desperation, as they have lost their livelihoods and are still awaiting government assistance,” Shamini Darshni Kaliemuthu of FORUM-ASIA said in a press release this month.

Homeless charities in Italy have urged police in some cities to stop fining rough sleepers for breaching self-isolation measures.

A spokesman for the interior ministry said that after a somewhat “jumbled” start to the lockdown, it instructed all local authorities to act in a “humane and rational way” when dealing with homeless people.

In the Indian capital of Delhi, homeless people have been prevented from walking outside to get to the “hunger relief centres” that have been set up to feed the needy during lockdown, according to the Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN).

The non-profit estimates there are up to 200,000 homeless people in the city.

Kale, the woman living in the Delhi shelter, said “we have heard that homeless people have been rounded up by the police from the streets and taken to camps. Some were beaten, some could not take their belongings”.

Rights groups in the United States said some police have been going against the advice of health authorities by continuing to enforce laws that prohibit trespassing and sleeping in or setting up tents in public places.

With libraries, cafes and other public facilities closed, it has become more difficult for homeless people to access toilets.

That makes it harder for them to follow basic sanitary guidelines such as handwashing, said Eric Tars, legal director of the Washington-based National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty.

It has also exposed some homeless people to fines for public urination, he said in a phone interview.

Cramped

As many U.S. homeless shelters are reducing their capacity to comply with social distancing orders, finding a safe haven has become almost impossible for many homeless people, Tars said.

“In some of the bigger cities, they are trying to address that. But so far, it’s been largely through creating new congregate facilities, which are not safe at all,” he said, noting that cramped conditions heightened the risk of contagion.

Authorities in India and South Africa have also set up impromptu shelters and camps, sometimes using stadiums and soccer fields.

But rights groups have warned that the conditions are often unsanitary and that police have been using force to bring homeless people to the temporary shelters or prevent them from leaving.

“The process of relocating them must be humane and not forceful,” said Shivani Chaudhry, executive director of the HLRN in Delhi.

“While several incidents of police assistance and goodwill have been witnessed during India’s lockdown, it is alarming that incidents of police brutality have also occurred in parts of the country.”

The Delhi police did not immediately respond to a request seeking comment.

Solutions

Homelessness advocates say the situation has improved in some cities as authorities have become more sensitive to the needs of homeless people.

In the Slovak capital Bratislava, early enforcement of social distancing rules by police sent homeless people scattering to hide in places like cemeteries and closed parks, making it hard for activists to help them, charities said.

But a week into the lockdown, the police became more lenient, said Pavol Sabela, manager of Stopa Slovensko, a non-governmental organisation.

Many of the homeless have now returned to the city centre, where it is easier to provide them with food, face masks and medical advice, he added.

In Barcelona, Spain, homeless people can get certificates stating that they have nowhere to live which they can show police to prevent them being fined for being outside, according to the Arrels Foundation, the charity that devised the scheme.

“Since we started doing the certificate – and police started to take into account that there are people living on the streets who don’t have a home to go to – the number of fines and complaints to the police has fallen,” said Beatriz Fernandez, the charity’s legal head.

Cities are also finding unconventional ways to house their homeless during the pandemic, turning vacant spaces and disused buildings – such as festival halls, conference centres and cottages – into makeshift homes.

Several cities have been mobilising public funds to lodge homeless people in empty hotel rooms, where they can safely self-isolate.

While most of these moves are short-term measures, they also provide an opportunity for some governments to reassess their general efforts to end homelessness, said Patrick Duce, campaign impact manager at World Habitat, a UK-based charity.

“In places like England, they have housed thousands of people in one week, when for years the government has said, ‘We will end rough sleeping and street homelessness by 2027’,” he said.

“Now we know it can be done. So, in the long term there need to be very serious conversations. If the money is there and the intention is there, why do we accept anybody sleeping rough?” —Reporting by Umberto Bacchi @UmbertoBacchi in Tbilisi and Rina Chandran @rinachandran in Bangkok; additional reporting by Kim Harrisberg @KimHarrisberg in Johannesburg and Sophie Davies @sophiedaviesed in Barcelona; editing by Jumana Farouky and Zoe Tabary.