KINGSTON, Jamaica — R as Iyah V. describes himself as confrontational, especially with the police.

Well known in Jamaica for his outspoken support of the marijuana industry, the Rastafarian — who sports a long, white beard and dreadlocks — has had various run-ins with the law over the years.

Authorities have long persecuted Rastafari, he said, including their sacramental use of marijuana, which Jamaica decriminalized for personal use in 2015.

“I have no intention of letting my rights be trampled on by the state,” he added.

Now, he is hopeful that a government program due to launch this month could lead to stronger rights for Rastafarians and help indigenous cannabis farmers benefit from the exploding global market.

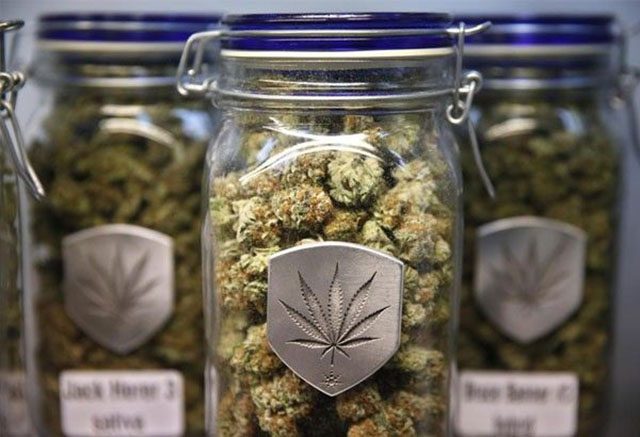

The Alternative Development Program (ADP) focuses on transitioning small, “traditional” cannabis farmers from illicit trade to Jamaica’s nascent formal industry.

It will provide land to cannabis farmers and subsidize the costs for the infrastructure they need to meet government licensing standards, said Floyd Green, state minister for industry, commerce and agriculture.

The aim is to encourage farmers to become licensed suppliers so they can sell the plant for research and development, as well as supply medical marijuana companies in Jamaica and Canada.

At the same time, the program will address longstanding issues of land ownership that have held back many indigenous farmers from joining the legal market.

The government said it wants to bring all of Jamaica’s cannabis farmers into the formal industry as it tries to tap into a global market that it estimates will be worth $50 billion within the next decade.

“We recognize that we have had traditional growers, and different parts of our societies have viewed the plant in different ways,” said Green.

“It is very important for us to move the illegal activity to a legalized trade,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in a phone interview.

Big business

According to the U.S. State Department, Jamaican farmers cultivate 15,000 hectares (37,000 acres) of cannabis every year.

Since decriminalizing marijuana — also called ganja, herb or weed — in 2015, Jamaica now allows citizens to grow up to five cannabis plants, while the possession of two ounces or less has been downgraded to a petty offense.

And the government has been granting licenses to farmers who want to grow cannabis for medical, therapeutic or scientific purposes.

The new policies also for the first time recognize the rights of Rastafarians to grow and consume marijuana as part of their faith.

Rastafarians, who make up less than two percent of Jamaica’s population of 2.9 million, have faced over 150 years of persecution, said Jalani Niaah, a professor at the University of the West Indies in Kingston who studies the Rastafari community.

While the new laws theoretically give Rastafarians more leniency, allowing them to possess and grow more than the general public, in practice, they still face obstacles to participating in the legitimate marijuana trade, said Niaah.

He pointed out that applying for a grower’s license costs $300 for an individual, which is more than many Rastafarians can afford.

For a business, the initial cost is $500. Depending on the type of license acquired, the annual fee can be up to $10,000.

“They (the government) are not giving Rastafarians a link directly to the industry,” said Niaah. “Unless you are a big businessman, you can’t compete.”

He said the government is capitalizing on cannabis while imposing impossible requirements on small farmers who have helped put Jamaican marijuana on the global map.

And he sees the new program as just another tool for exploiting the country’s small cannabis farmers: “The ADP is a grossly inadequate afterthought to an objectionable and exclusive economic design.”

Instead, Niaah would like to see the government fully legalize cannabis and support a national industry built specifically to benefit indigenous farmers.

Land ownership

Another group that struggles to access the now-formalized marijuana industry is the Maroons.

Maroons were Africans who escaped slavery and mixed with indigenous populations to form independent settlements.

The vestiges of the Maroons’ post-emancipation flight and the marginalization of Rastafarians mean much of the cannabis farming in Jamaica happens on land without a title, according to lawyer Grace Lindo.

Lindo, who specializes in intellectual property and has an interest in the patenting of marijuana strains, sees the ADP as a chance to start untangling the complicated relationship between Jamaicans and their land.

“A significant amount of land is unregistered in Jamaica and the ganja laws recognize that people may be using family land for which there is no title,” she said.

If the government helps indigenous farmers get titles to their land, “then Rastafarians will be further along in the application process” for cannabis licenses, she added.

Green, the state minister of agriculture and industry, said the difficulty of establishing land ownership is one reason the ADP still has not launched two years after it was first announced.

He agreed that proper titling of land is an essential part of the program.

Creating employment

Although marijuana advocate Ras Iyah V. supports the government’s efforts, he feels the ADP is not moving fast enough.

“The government is dragging its feet in terms of getting this program off the ground,” he said.

He noted that work has stalled on the 10-acre cannabis farm that was set up under the program in his community of Orange Hill, 100 miles (160 kilometers) west of Kingston.

Tired of waiting, he has launched a crowdfunding campaign to help raise funds for fencing, security, irrigation and other things it needs to meet government standards.

When the program finally launches, he can see it benefiting his community, and others all over Jamaica, for generations.

“Jamaica has a heavy unemployment rate, and a lot of youths out there who just don’t have anything to do,” he said.

“This could create employment and give ownership to grassroots people.”

— Reporting by Kate Chappell; Editing by Jumana Farouky and Zoe Tabary (Thomson Reuters Foundation)