TANAY, Philippines – In one of the classrooms in Rawang Elementary School, Municipality of Tanay, a handful of teachers have taken on the role of pupil, as they listen to Korean academic Hyun-woo Kim explain the workings of a rainwater harvest facility in the school yard.

It is the middle of summer, and Mr. Kim is sweating, his face pink. The teacher-in-charge, Mrs. Catherine Resurreccion, offers him a paper cup filled with cold water, which they had brought along in a thermos. He gulps it down, but can’t have too much, as this is the only source of water on campus. The creek, where residents of Brgy. Tandang Kutyo usually get their drinking water, is a five- to fifteen-minute walk away.

Thankfully, the rainwater harvest facility he designed, with the help of his mentor, Professor Han Moo Young from the Seoul National University (SNU), is set to be launched in June, to coincide with the start of the schoolyear. Construction began in January and ended in March; all that’s left to do is test the quality of the drinking water according to Philippine standards.

Mr. Kim, a water quality researcher from SNU, had been working since September last year with the teachers and students; the local government; Philippine NGO Institute for Global Education, Exchange, and Internship; Hyundai Korea, which initiated the project as part of its corporate social responsibility; its partner BetterWorld; and its local arm HARI Foundation.

A system that would turn rainwater into drinking water was a simple way to provide a remote community access. Spring water could be tainted by heavy metals and other contaminants, but rainwater was clean, Mr. Kim explained in an interview with InterAksyon. As long as the school roof, which served as the basin, was kept clean, the rainwater collected could be easily purified.

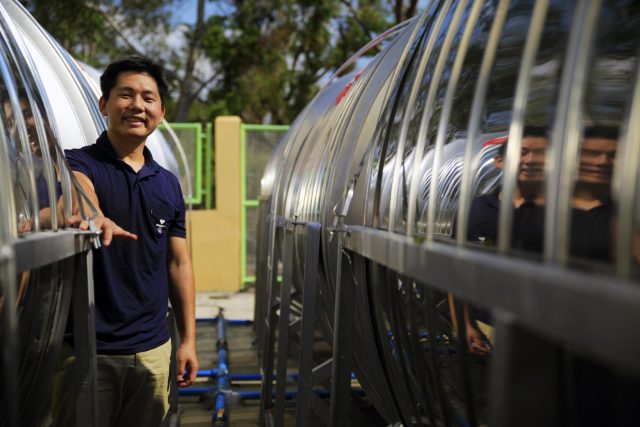

The rainwater harvest facility had a screen attached to the roof, which would prevent branches and other large items from getting into the water. The water would then flow into six storage tanks. As it gushed from tank to tank, sediments would be left behind, purifying the water. It would then run through three filters that would trap tiny particles, and finally, the ultraviolet (UV) filter, which would cleanse the water even more.

A water meter would show the amount of water in the tanks. Five faucets were attached to the system, from which the potable water would flow, with the help of a water pump. Another faucet was for ordinary use.

“This is the most difficult project for me because it’s a very big mountain, and there’s no water, there’s no electricity,” Mr. Kim said. “It’s actually a very, very difficult situation for the construction. It’s very challenging.”

As the area was above the Calinawan Cave, construction workers had to clear the site of boulders, wrecking two backhoes and a number of pickaxes in the process. Water was another problem, as the local supplier was far from the site. The UV filter and water pump couldn’t function without electricity either, so Mr. Kim and other partners had to buy a diesel-fueled generator.

“I was able to do it with the people who helped me. The engineers, the governor, the NGO, the teachers, and people living here. They all helped me… If was alone here, I could never accomplish this,” he said.

He arrived in the community worried that he would be spurned, but the local government was receptive, as they saw the value of the rainwater harvest facility. He had become dear to the kids, as well, with them shouting, “Mr. Kim!” whenever they’d catch sight of him.

“The residents love him. He’s the only person they know out of all the people who come here, since he’s the most visible of them. He’s always smiling, he’s always here, and he’s always approachable,” Mrs. Resurreccion related.

One hundred and thirty-one pupils from kindergarten to Grade 6 would benefit from the project, along with the faculty, school personnel, and parents. The community was also considering selling the drinking water in the future, to cover maintenance expenses. The diesel for the generator, for example, had to be funded.

Despite the new facility, Mrs. Resurreccion had more burdens to bear: the lack of electricity and water for ordinary use in the newly constructed elementary school building. The old building, which had been standing since 1982, was already termite-infested, and was on land just lent to them by the owners of Calinawan Cave. After previous school administrators wrote letter after letter to the local government, the latter finally relocated them, although there were still problems with the land, as it was still being expropriated.

Mrs. Resurreccion planned to keep writing the local government to ensure that there would be electricity and water in the new building in time for the new schoolyear. “‘Di bale nang makulitan (Never mind if they find me a nuisance),” she added.

She had only good things to say about the donors, NGOs, and technical experts.

“Thank you for choosing us.”