When the “The Exorcist” premiered 50 years ago, in December 1973, some theatergoers fainted or broke down in tears. A few even vomited.

The film, which cast a young Linda Blair as a girl claiming to be possessed by the devil, was an almost instant success, with moviegoers waiting in line for hours to secure tickets. It went on to gross over US$440 million worldwide.

The horror film eventually received two Oscars, for Best Sound and Best Adapted Screenplay.

In the 50 years since, the cultural fascination with Satan has persisted. But as religiosity has waned, popular portrayals of Satan have also changed. Rather than embody pure evil, Luciferian characters that are complicated – even likable – have emerged.

Cinema’s dance with the devil

The devil has never been a stranger to the movies. He appeared as early as 1896, in Georges Méliès’ “The House of the Devil, a three-minute silent film.

Just five years before the release of “The Exorcist,” Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby” told the story about a young woman, played by Mia Farrow, who was carrying Satan’s child.

That film also took home two Oscars. Still, critics generally credit “The Exorcist” with kicking off a run of movies about Satan and demonic possession.

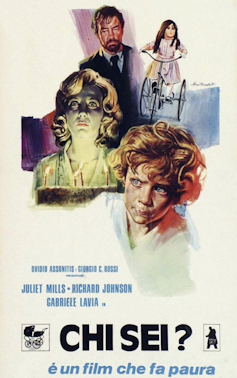

Wikimedia Commons

Imitations appeared all over the world. There was the 1974 Italian film “Beyond the Door,” starring Juliet Mills as a young woman pregnant with the Devil’s baby. The Turkish film “Seytan,” which told a story almost identical to “The Exorcist,” was released that same year. The 1976 film “The Omen” and its sequels imagined the rise of Satan’s son, Damien Thorn.

Other filmmakers showcased the versatility of the subgenre by imagining Satanic encounters everywhere from cruise ships to schoolyards. Jack Starrett’s “Race with the Devil” told the story of vacationers fleeing a Satanic cult. A slew of TV movies also appeared, such as “Satan’s Triangle” (1975) and “Devil Dog: The Hound of Hell” (1978).

Interest in exorcisms surges

Anxiety about social change and growing secularism gave “The Exorcist” influence beyond the box office.

In November 1973, a month before “The Exorcist” premiered, The New York Times reported that among U.S. Catholics, attendance at weekly mass had dropped to 48% from 61% between 1972 and 1973.

After the movie came out, curiosity about Catholicism rose significantly.

This was especially true with regard to exorcism, a rite so rarely practiced within the church that the film’s protagonist, Father Damian Karras, says that in order to find someone to perform it, he’d “have to get into a time machine and get back to the 16th century.”

Nonetheless, in January 1974, The New York Times reported that the Catholic Church was receiving “a wave of inquiries from persons who believe that they, or their acquaintances, are possessed by demons.”

Many of these requests came from people who were no longer, or never had been, churchgoers.

Fears of satanism snowball

“The Exorcist” and its imitators were very much still in the zeitgeist during the satanic panic of the 1980s, which involved thousands of false accusations of Satanic ritual abuse throughout the U.S. and Canada.

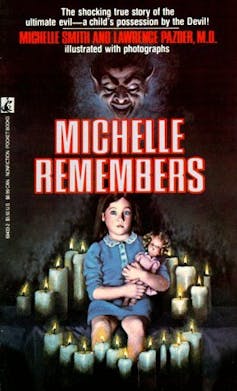

In 1980, “Michelle Remembers,” a memoir about a young woman’s sexual abuse by a satanic cult, was published. Though it was eventually discredited, the book is thought to have kicked off the panic.

Goodreads

Throughout the 1980s, reports of satanic rituals and abuse reached hysterical levels, perhaps most famously in Saskatchewan, Canada, where day care workers were accused of satanism and sexual abuse. Major media networks capitalized on fears of a fallen world, with NBC running a 1988 special entitled “Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground.”

Meanwhile, accusations of satanism were leveled at everything from “Dungeons & Dragons” to heavy metal music. Some people even believed the conspiracy theory that the Proctor & Gamble logo contained hidden satanic symbols.

Sympathy for the devil

By the turn of the 21st century, the panic had run its course, as had representations of Satan as an embodiment of pure evil.

Growing secularism in the U.S. ran in parallel with depictions of a charming, more likable Satan. The public had grown increasingly disillusioned with institutionalized religion, especially with revelations of child sexual abuse within the Catholic Church and other denominations.

This sympathy for the devil was nothing new: It went back at least as far as John Milton’s 1667 epic poem “Paradise Lost.” The poem’s depiction of Satan as the fallen angel Lucifer was so compelling, it caused poet William Blake to famously suggest that Milton was “of the Devil’s party without knowing it.”

“Paradise Lost” has been adapted and reworked for modern audiences.

The television series “Supernatural” includes a number of story arcs featuring a dangerous but charismatic Lucifer. The figure is also depicted sympathetically in Neil Gaiman’s “Sandman” comics.

The 2015 film “The Witch” takes a different approach, portraying communion with the Devil as preferable to a life of drudgery and abuse for teenage girls in Puritan New England.

Meanwhile, satanism has emerged as a secular movement. According to the Satanic Temple, its members seek to “encourage benevolence and empathy” and “reject tyrannical authority” to protect the separation of church and state.

Everyday evil

Still, neither sympathetic narrative portrayals nor secular movements have fully diminished the power of Satan to trouble the popular imagination.

In a society that has become increasingly divided, satanism has once again become a potent source of fear. The internet is rife with rumors about the supposed satanic origins of Halloween and the “Harry Potter” books. Echoes of the satanic panic can be found in the QAnon movement, which accuses some Democratic politicians of a satanic conspiracy to kidnap and sexually abuse children.

The hysteria expressed by groups like QAnon is an extreme example of a long-standing human impulse to label those who are feared and hated as personifications of evil. At the same time, this tendency is a way to understand the horrible cruelties of this world, and why people inflict such harm on each other.

During the original run of “The Exorcist,” many people questioned the impulse to embody all evil within a single supernatural figure. In a 1974 interview about the film with The New York Times, priest and psychologist Eugene Kennedy noted that it’s important for people to “[come] to terms with our own capacity for evil, not projecting it on an outside force that possesses us.”

This sentiment remains true today. Everyday acts of evil, small and large, may be easy to ignore when measured against the so-called “pure evil” embodied in the character of Satan. Nonetheless, the undiminished cultural fascination with the figure of Satan may be a way of trying to better comprehend evil – and why people so often choose it.![]()

Regina Hansen, Master Lecturer of Rhetoric, Boston University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.