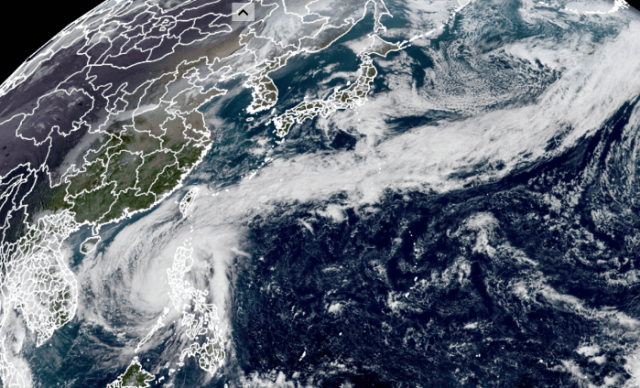

(Updated 7:05 p.m.) Typhoon Ulysses (international name Vamco) that scraped the Philippines overnight on Thursday looked like it was attached to a giant cord of clouds and air that stretched across the North Pacific and reaching the other side of the world.

The tail, however, is a separate phenomenon called a stationary front. Dr. Gerry Bagtasa, an atmospheric physicist and professor, explained that this weather front is formed when cold winds from Siberia moving southward meet the warm and moist air of the tropics during amihan season.

“Sometimes, the tip of this front affects the Philippines and is what PAGASA refers to as the ‘tail-end of a cold front,’ because only its tail-end affects us. The flooding in Claveria or Aparri around a week ago (or so) was due to this,” Bagtasa wrote in an email to Interaksyon.

“When Typhoon Ulysses moved westward, it seems that they are connected. The typhoon can form without the front and fronts can form without any typhoons, so they are independent,” he added.

Interaksyon estimates that the stationary front measures about 9,500 kilometers from the Philippine area of responsibility to the Gulf of Alaska.

Weather expert @weather_manila tweeted a reaction to this report, which earlier claimed the front was attached to Typhoon Ulysses.

“The typhoon and the stationary front are two, totally different things, and have nothing to do with one another,” wrote the Twitter account, run by Bagtasa.

The phenomenon is still a marvel when seen from a satellite’s point of view.

“Typically, the front is not that long, usually just from north of Luzon to the southeast of Japan. But due to some weather patterns around Japan and the northern Pacific ocean, this front is currently very long, it is actually rare that it’s this long,” Bagtasa wrote.

A stationary front is a cold or warm front that stopped moving due to “two masses of air pushing against each other, but neither is powerful enough to move the other,” according to the website of UCAR Center for Science Education.

“A stationary front may stay put for days. If the wind direction changes, the front will start moving again, becoming either a cold or warm front. Or the front may break apart,” it added.

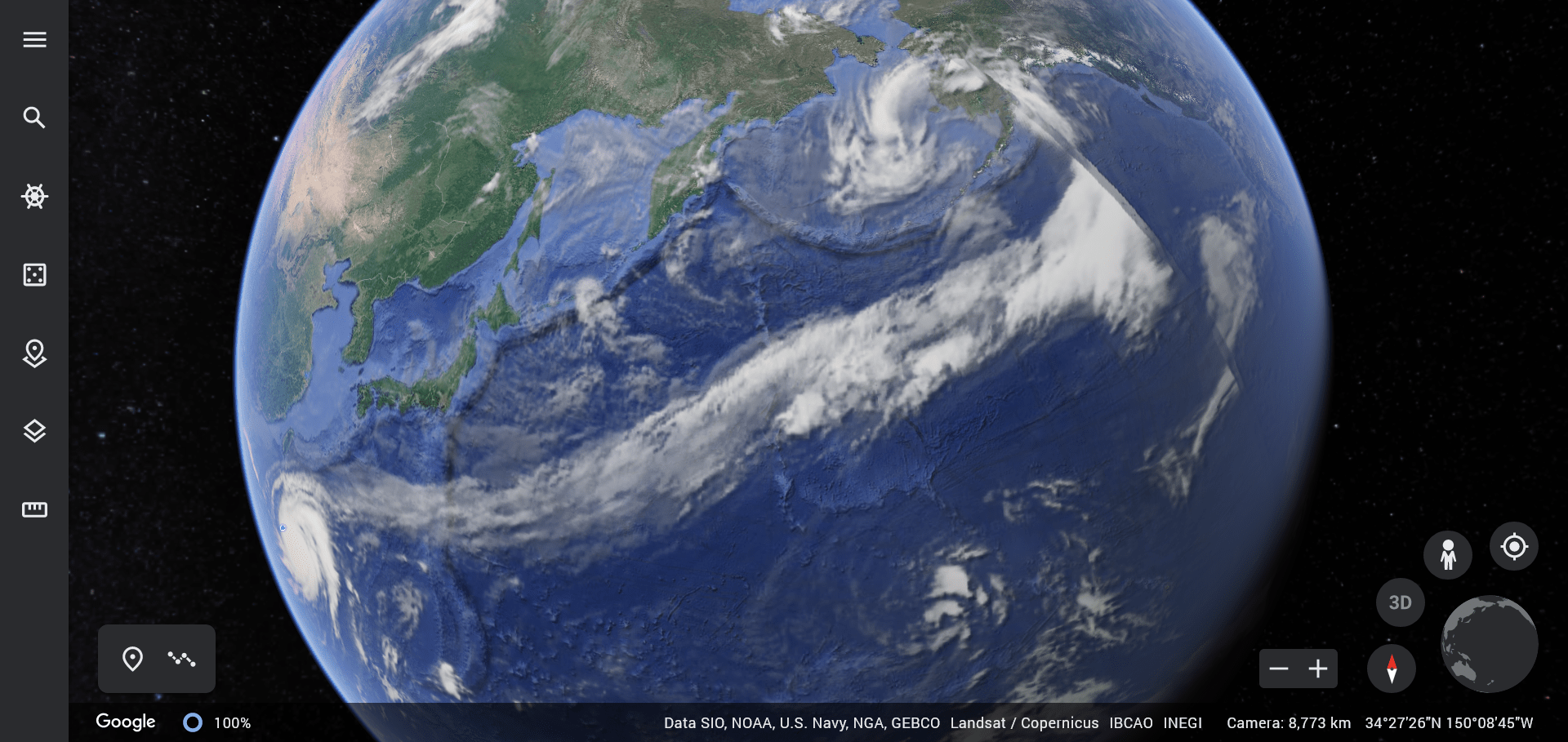

The front takes on a shape of a question mark as if emanating from Ulysses’ spiraling rain bands. You can see it in action on Google Earth. (Check it out now before it’s gone.)

British filmmaker and storm chaser James Reynolds likens it to a “umbilicus.” “The atmosphere never ceases to amaze!” he tweeted.

#typhoon #Vamco, with an umbilicus stretching 1000s of miles across the North Pacific connected to a grotesque “mother ship” low lashing Alaska – the atmosphere never ceases to amaze! pic.twitter.com/0gj2jqMpzY

— James Reynolds (@EarthUncutTV) November 11, 2020

At its peak, Ulysses was packing maximum sustained winds of up to 155 kilometers per hour near the center and gustiness of up to 255 kph as it made a third landfall in General Nakar at 2 a.m.

The mountain range of Sierra Madre hardly diminished its typhoon status and made its way to western Luzon and drenched the regions of Metro Manila and Calabarzon.

Editor’s Note: Updated with explanation for the phenomenon, correcting the earlier report that the stationary front was generated from the typhoon.