Most public restrooms are grungy in the best of times. Now, we have the coronavirus risk to contend with, too. There are lots of risks – dirty sinks and door handles, airborne particles and other people in small, enclosed spaces who may or may not be breathing out the coronavirus.

So, how do you stay safe when you’re away from home and you’ve really got to go?

As a medical doctor and epidemiologist, I study infectious diseases involving the gastrointestinal tract. Here are four things to pay attention to when it comes to any public restroom.

What goes into the toilet doesn’t always stay there

Have you ever thought about what happens when you flush a toilet?

Scientists who worry about disease transmission in hospitals have, and their findings are worth remembering when you’re in a public restroom.

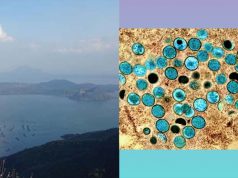

All that bubbling, swirling and splashing can aerosolize fecal waste, sending tiny particles airborne. A study on hospital bathrooms found that the amount of those particles spiked after a toilet was flushed, and the concentration in the air remained high 30 minutes later. It didn’t matter if the test was done right next to the toilet or 3 feet away. Second and third flushes continued to spread particles.

Researchers have found that the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, can be shed in feces for up to a month after the illness. That’s longer than in respiratory samples, though how much of that time the virus could be causing infections and whether the virus has infected humans through fecal waste isn’t yet known.

Surfaces can harbor the virus, so wash up

The aerosols generated when someone infected with coronavirus coughs or even talks can be inhaled, of course, but they also settle out on surrounding surfaces, such as bathroom counter tops.

To stay safe, be extra careful and touch as little as possible in public restrooms, including door handles. Whatever you do, don’t touch your eyes, nose or mouth after touching these surfaces – your mucous membranes are the coronavirus’s entryway into your body.

When you’re done, thoroughly wash your hands with soap and water, and maybe skip the hot-air hand dryer, which can also create aerosols and blow them toward you.

Carrying face masks, hand sanitizer and disinfectant wipes with you can help you be prepared, particularly if the facilities lack soap or running water.

Enclosed spaces are a problem

The air in an enclosed space like a public restroom can have coronavirus particles in it for several hours after someone infectious with COVID-19 was there.

Scientists still don’t know how much of the virus you have to take in to become infected, but it’s better to be safe than sorry. Limiting the amount of time spent in any enclosed indoor space – restrooms and restaurants included – can reduce the potential for getting sick from the coronavirus.

Wear a mask, and walk out if others aren’t

One of the more insidious characteristics of the new coronavirus is that someone infected with the virus can be spreading it two to three days before they show any symptoms. Some people don’t show symptoms at all, but they can still be infectious for days.

Based on surveillance during the Princess cruise ship outbreak in Yokohama, Japan, 15 to 20% of the people tested positive for the coronavirus had no symptoms. Data from Wuhan, China, put the number of asymptomatic cases at closer to 40%.

Keeping at least 6 feet away from others and wearing a mask can help you avoid spreading the coronavirus if you’re asymptomatic and don’t realize it. They can also help protect you, though social distancing in small public restrooms isn’t always possible.

If someone else is in the restroom without a mask on, the best advice is to walk out. It isn’t worth the risk.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

William Petri, Professor of Medicine, University of Virginia. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.