In 1917, then budding filmmaker Jose Nepomuceno established Malayan Movies, the first Filipino film production outfit. Two years later in 1919, the company produced the first ever Filipino silent film, “Dalagang Bukid,” headlined by the legendary Atang de la Rama, who went on to become a National Artist.

Thanks to the pioneering venture of the man now known as the Father of Philippine Cinema, generations of filmmakers and moviegoers alike have seen how much Filipino films have progressed for the last 100 years.

The history of Philippine cinema has gone through varied, and often tumultuous, periods. Starting during the colonial period under Spanish and American rulers, it has survived a cataclysmic war under the Japanese, enjoyed a boost during the post-war independence, went through the period of martial law, and has transformed in the contemporary digital era.

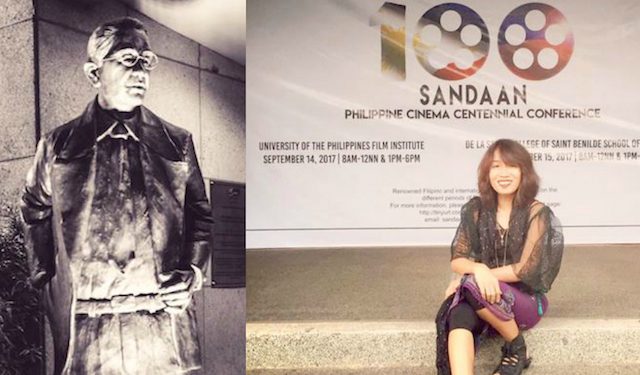

To celebrate this momentous centennial of Philippine cinema, the University of the Philippines Film Institute, in cooperation with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the Film Development Council of the Philippines, and in partnership with De La Salle-College of St. Benilde, organized the “Sandaan: Philippine Cinema Centennial Conference.”

Filmmaker Sari Dalena (“The Guerilla is a Poet”) of the UP Film Institute and “Sandaan” project director told InterAksyon that the two-day conference is the first of a three-year celebration that will culminate in 2019 with the centenary of Nepomuceno’s “Dalagang Bukid.”

“‘Sandaan’ looks at our cinematic history, from 1917 to the present, re-imagining our lost cinema during the pre-war years beginning with Jose Nepomuceno, the Father of Philippine Cinema’s establishment of his film studio and the evolution of Philippine cinema as it was shaped by our nation’s turbulent history, through the lens of film scholars, exploring significant works from various periods, its issues and representation,” she noted.

“In the margins of cinematic history, we also celebrate the small, invisible films that were created outside of the studio system that fed the spirit of independent cinema.”

As organized by conference directors Patrick Campos and Nick Deocampo, the first day of the conference took place Thursday, September 14, at the UP Film Institute Film Center or Cine Adarna with University of Hawaii academician and Asian cinema chronicler Wimal Dissanayake as keynote speaker.

Several panelists covered the topics of Early Cinema to Prewar, Prewar to War Years, Postwar to Pre-1972 and Martial Law & Political Cinema. The event culminated with a screening of Kidlat Tahimik’s pioneering independent feature, “Perfumed Nightmare,” which this year is celebrating its 40th anniversary.

The second day of the conference happened the next day at the De La Salle-College of St. Benilde School of Design and Arts Theater and covered Regional and Diasporic Cinema, Digital & New Cinema, Subaltern and Activist Subjects, Film Education, and Alternative Histories.

During the evening, the FDCP, in cooperation with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), also hosted “Sandaan: Appreciation and Tribute Night” for Don Jose Nepomuceno. The event was held at the Cinematheque Centre Manila.

The “Sandaan” festivities culminated with a special screening of Tony Cayado’s “The Big Broadcast,” the first Filipino feature film to be shot in full Technicolor. The film, released by Sampaguita Pictures, is celebrating its 80th anniversary this year.

Further reflecting on the anniversary celebration, Dalena ponders on the rosy outlook of Philippine cinema and anxiously looks forward to what the future holds for the resurgent film industry.

“Cinema is a beautiful, powerful instrument and it is young at 100 years. Film has given us so much, and as an art form, it remains to be explored, shaped, discovered in the next hundred years,” she muses.

“As ‘Sandaan’ revisits the history of our cinema, we ask ourselves: what will our filmmakers be dreaming of in the next one hundred years? For whom do we make films? Is this the end of cinema? Or just the beginning?”

“May this convergence of scholars, filmmakers and lovers of cinema be a time for reflection, break new ground for the next hundred years, and revel in its beauty and power in capturing the spirit of our people,” the filmmaker concluded.