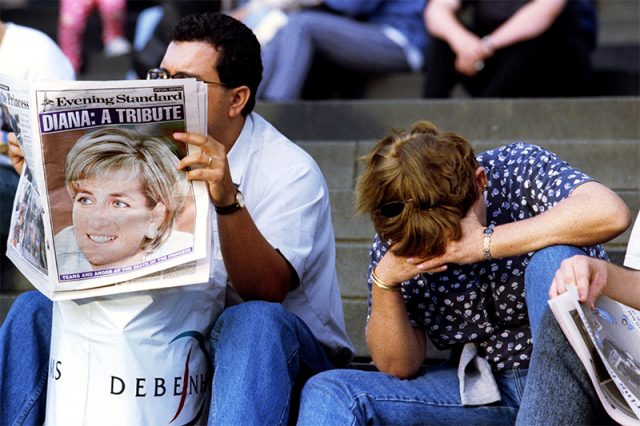

Diana, Princess of Wales, died 25 years ago after a car crash in the Pont de l’Alma tunnel in Paris. Her death led to a global outpouring of grief and media attention. Much of the public reaction criticized the royal family for what many saw as an unfeeling response to the sudden death of the Prince of Wales’ former wife.

The shock of Diana’s death also sparked countless conspiracy theories. Decades later, many have not given up the idea that Diana may have been the victim of a plot.

Unexpected events, such as deaths or accidents, are fertile breeding ground for conspiracy theories, which allow people to make sense of chaos by finding evidence, coincidences and someone to blame.

Celebrity deaths have inspired an entire genre of conspiracy theories, particularly the death of Princess Diana. While conspiracy theories about Diana’s death may hinge on different, specific details about the circumstances surrounding the fatal crash, many reach the same conclusion – that she was murdered by the royal family or the British authorities.

I study conspiracy theories to find out why people believe in them. One of the questions I ask is about the language of celebrity death conspiracy theories, and why it is so persuasive.

Conspiracy theories are empowering for people, allowing them to become DIY detectives. These “detectives” approach a case having already arrived at their conclusion. In celebrity deaths, this usually means murder by someone who seemingly benefits from the death.

An official inquiry, like Operation Paget, which was set up by the Met police to investigate conspiracy theories about Diana’s death, asks what happened. The conspiracy detective, on the other hand, asks cui bono – who benefits.

Palace intrigue

The basis of many conspiracy theories is what’s known as “teleological thinking”. This is when someone assigns a specific function or meaning to occurrences or inconsistencies. For conspiracy theories, this means that there is no space for imperfect systems, human error or random coincidences.

The circumstances of Diana’s death were confusing and chaotic at the time, precisely because of likely mistakes and human error. For years, conspiracy theorists have raised questions about these, asking: Why did the ambulance take so long to get to the hospital? Why did emergency responders clear the tunnel so quickly? And, why were the surveillance cameras not working?

A mind primed to look for conspiracy will say these were deliberate actions to worsen Diana’s condition or hide evidence of a murder. Reality, as is often the case with conspiracy theories, is more mundane. The conclusion of the Paget report, based on all available evidence, was that Diana’s death was the result of a tragic accident – not a conspiracy.

When there is a lack of irrefutable evidence, insider speculation can act as a replacement. For instance, Mohammed Al-Fayed, father of Dodi (Diana’s lover, who also died in the crash) publicly accused the royal family of murder. This led to Operation Paget, which refuted the claims but, nevertheless, did not appease those conspiracy theorists who distrust any form of official evidence.

Conspiracy theorists use different types of evidence, including so-called premonitions and psychic predictions. Some claim Diana foresaw her own death, based on the publication of a letter, she had supposedly written to her former butler Paul Burrell, which read: “my husband is planning ‘an accident’ in my car”. And Diana’s spiritual adviser claimed to have warned her brakes would be tampered with. The Paget investigation found no evidence for these claims.

Before her death, in the infamous 1995 BBC interview with Martin Bashir, Diana claimed that those within the royal household “see me as a threat”. However eerie or striking these “premonitions” and insider testimonies seem, none of these claims in and of themselves prove the theories that she was murdered.

The promise of conspiracy

Theories about Princess Diana contain a key hallmark of conspiracy: an in-group and an out-group. While typically, celebrities like Diana and the royal family would be seen as part of the in-group in contrast to the public outsiders, these labels mean something different in the context of conspiracy theories. The in-group in this case are the general public and Diana. They represent good, with Diana characterised as a victim. On the other hand, the out-group – the royal family and authorities – are the villains: a powerful and evil threat to the in-group. The out-group is where the conspiracy theorist can identify potential culprits.

Diana conspiracy theories often hinge on people not following procedure, and comparing a supposed conspiracy against an ideal scenario (what should have happened). The conspiracy detective assumes that nothing goes wrong without malicious intent. Uncovering the supposed lie, cover-up or conspiracy is therefore a way for the victims and their allies (the in-group) to regain power over the out-group.

Celebrity death conspiracy theories are palatable for a mainstream audience, because they allow a traumatic or confusing event to become “clear”. They offer us a glimpse of a perfect world to hope for, where nothing ever goes wrong and humans make the best choices they can at any given point. And, had the evil out-group not conspired to murder her, Diana might still be here today.![]()

Sarah Bennett, PhD candidate, School of English, University of Nottingham. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.