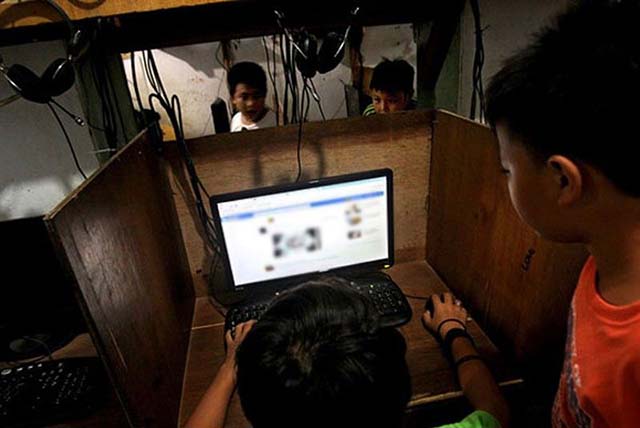

MANILA (Thomson Reuters Foundation) — It was the half-naked girls running from room to room upon her arrival that made Filipina teenager Ruby fear the cyber cafe job she had been offered online might in fact be a sinister scam.

Ruby’s doubts turned to despair when her new employers — a husband and wife — dragged her in front of a computer and webcam and explained that her work would entail stripping and performing sex acts for paying customers across the globe.

“It was like a bomb exploded,” Ruby, now 21, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in an empty church in Tagaytay city in the Philippines. “I had seen cybersex dens in TV shows and movies, but I didn’t know that they existed in real life.”

“I had been totally fooled,” Ruby added. “I was forced to do things you could not imagine a 16-year-old having to endure.”

Ruby is not a rare case but one of a rising number of ever-younger victims of cybersex trafficking — a form of modern-day slavery where children are abused and raped over livestreams.

The Philippines is seen by rights groups as the epicenter of the growing trade, which they say has been fuelled by access to cheap internet and technology, the high level of English, well-established money wiring services and rampant poverty.

The Southeast Asian nation receives at least 3,000 reports per month from other countries of possible cases of its children being sexually exploited online — a number which has tripled in the last three years — according to its justice department.

Yet the crime is difficult to police as most victims are exploited by their own relatives in a country with very high levels of sex abuse within families and a culture of silence in communities that stops people speaking out, campaigners say.

And Filipino abusers and paying clients, from Australia to Canada to Germany, are outfoxing law enforcement by mixing up payment methods, turning to cryptocurrencies, and broadcasting over encrypted livestreams which cannot be traced by police.

The crime is not only growing in the Philippines, but across the region, from Cambodia to Vietnam, as the standard of English and access to technology and internet improves, activists said.

“This is a global trend — but very evident in Southeast Asia,” said Damian Kean, a spokesman for End Child Prostitution and Trafficking (ECPAT) International, a network of charities.

“We are seeing online sexual exploitation of children expand across the region.”

Touching to torture

Victims in the Philippines are getting younger as poverty drives families to abuse their children in exchange for money from clients around the world, said Lotta Sylwander, country director for the United Nations children’s agency (UNICEF).

Abusers can earn up to $100 per show in a country where about a fifth of its 100 million people live in poverty — earning less than $2,000 a year — government figures show.

“Exploitation begins online … but often leads into offline physical sex exploitation (and) trafficking,” Sylwander said.

The biggest obstacle to tackling the crime at its source is a widespread belief within communities that making children appear naked on webcam is a victimless act, rights groups say.

“Some families say: ‘We don’t touch, we just show’,” said Sam Inocencio, national director for the International Justice Mission (IJM), an anti-slavery charity. “But we have seen some awful cases where children have been tortured over webcam.”

Driving through the narrow, winding streets of a crowded slum in Manila, local police investigators pointed to rows of ramshackle homes crowned with gleaming white satellite dishes.

At least 40 percent of the Filipino population had access to the internet as of 2015, up from a quarter in 2010, and about 5 percent in 2005, according to World Bank data.

Activists are trying to challenge community-wide complicity in the crime by encouraging local council and church leaders, neighborhood watch groups and social workers to report abuses.

Yet contradictions between various laws, few convictions for cybersex trafficking, and the fact the age of sexual consent is 12 have all fuelled long-entrenched impunity, campaigners warn.

“People are not aware of the severity of the crime … they need to know the laws and their punishments,” said Genesis Jeff Lamigo, a spokesman for global children’s charity World Vision.

No data exists on the number of child victims of cybersex trafficking, but at least 400,000 people in the Philippines — or one in 250 — are estimated to be trapped in modern slavery, found the 2016 Global Slavery Index by the Walk Free Foundation.

Tracking tech trends

The plethora of social media sites, messaging and video call apps and online payment services make it easy for Filipinos to connect with global buyers and stream sex abuse undetected.

“The facilitators are following trends in technology,” said William Macavinta, a police chief superintendent in Manila.

“This makes tracking them more difficult — it is a challenge to gather digital evidence,” he added, explaining how anti-money laundering and cybercrime officials help police to chase leads.

Web and online money companies must do more to spot abusers, yet criminals can easily jump between platforms, said a U.S. investigator who tackles cybersex trafficking in the country.

Joint operations with nations such as Britain, the United States and Norway could swing the tide as clients realize they can be punished at home, added the investigator, who did not disclose his name as he was not authorized to discuss his work.

Senator Loren Legarda urged tougher global action from such countries to lower the demand by raising their penalties.

“Developed countries, from which the demand for online sex exploitation usually originates, must do their part,” she said.

But with cybersex abusers and customers playing a game of cat-and-mouse with law enforcement, Ruby fears that countless other girls will have to endure the same abuse as she did.

While Ruby has been able to rebuild her life with the help of the IJM — she is studying English with hopes of becoming a lawyer —as she escaped slavery after two months, she wept as she recalled the suffering of other girls trapped in the trade.

“They didn’t feel any shame … they didn’t value themselves,” she said.

“Those girls were in a place where they really had no hope.” — Reporting By Kieran Guilbert; Editing by Katy Migiro