(This piece on veteran journalist Rolando Espina, who passed away in Bacolod City this week, was originally posted in Nonoy Espina’s FB account)

My early memories of Daddy (yeah, I know, he was Daddy and she was Nanay – a class divide if ever there was one) come in snatches, some fleeting, some impossible to forget.

There was the night I was awakened in our home on Lakas ng Bayan in Pasay by loud bursts and flashes of light and furtive shadows scurrying over rooftops on nearby Taft Avenue … an uncle hastily snatching me from the top bunk and bundling me downstairs … then Daddy and Nanay rushing into the house disheveled, their clothes bloodstained, and after a few minutes to freshen up, rushing out again. That was the night of the Lapiang Malaya march and the two of them, I later learned, had posted themselves in the courtyard of San Isidro church: Dad to, what else, cover the event, Nanay giving first aid to casualties, most of whom Dad had dragged to safety.

Then there was the morning during the campaign for Marcos’ second term when I came down in my jammies on my way to the kitchen and passed a couple of uncles (Yup, our homes have always had spare kin around, still do … extended family’s a thing with us) outside the basement where I often played but whose door that day was sealed up by bales wrapped in old newsprint, the both of them whispering about how they could take one bale and no one would be the wiser, when Dad drops in and shakes his head, saying whatever it was in there wasn’t for us and taking it would likely bring bad mojo down on everyone. Later learned it was OOOOODLES of cash left in his care by his Tiyo Nanding Lopez, yup, the soon-to-be dictator’s soon-to-be royally screwed running mate who, Dad would mischievously say, “insists we’re related” but with whom he had a really close relationship.

And there were days he’d take me with him to work at the pre-martial law Chronicle, where I first smelled the heady scent of printer’s ink and newsprint and hot metal casts, and then sneak me into Taboy’s Cinco Litros where I’d stare in wonder at the boozed newshounds and buxom damas while the lord of the casa belted out naughtiness with his guitar.

And him campaigning for his second term as National Press Club vice president to his kumpare and soon-to-be revolutionary hero, then NPC president Antonio “Antumel” Zumel, wearing a T-shirt showing Da Apo covering his nether regions as he perched on a toilet seat and proclaimed: “I love Dovie Beams!”

Then our ever growing brood’s move from Manila to Bacolod, and the crammed family outings in the beat-up Corona and, later, the even more beat-up Harabas when a cacophony of voices belting out songs from Danny Kaye’s fairy tale songbook or Mary Poppins, the Singing Nun, the walang kamatayang Sound of Music and even – gasp! – Moon River as sung by Andy Williams or trying to emulate Mantovani’s treacly strings drowning out coughing, wheezing, gasping engines straining to ferry a dozen souls in space meant for half.

Of course, nothing’s too good it doesn’t end and growing up eventually led to … BOOM!

Ours was the clichéd love-hate relationship between headstrong father and son. Our clashes were epic, filled with fire and brimstone. And, of course, I was adamant about NOT following in his footsteps.

But looking back, I suspect he knew that, after bumming around trying – and failing – to make a career squeezing what I could from paltry creative juices, I’d come around and, indeed, I did when the time came to find a job that would feed the body, the only job I really was good enough at … what else, following in his footsteps. And I am pretty sure, though we continued to crash against each other, he was also certain I’d eventually realize that it was a job that would end up feeding the soul more than the body but a damned job that I would come to love by the time that happened.

In the end, I knew we’d reached the point of, if not exactly friendship yet, at least mutual if, at times, grudging respect for each other’s points of view when, one day, in our apartment in Manila, I walk in on him with an unusual afternoon glass of Scotch in his hand and he waves to me to sit and pours me a shot then quips: “You know, if it wasn’t for me, you probably wouldn’t be around.” I look up, then shoot back: “I guess if it wasn’t for us, too, the same could be said for you.” And then we laugh long and loud and crash our glasses together and that Scotch goes down in record time.

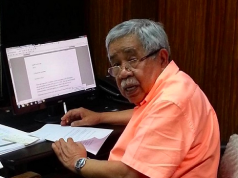

And since then, meetings would typically be we two trading notes and points of view about what was happening, seldom agreeing on anything at first but, surprisingly, as the years went by, he more often agreeing with my views than not and I more accepting of his. And he even took to marching and speaking with us in the streets in defense of press freedom (see accompanying picture), often breaking out in an impish grin when he saw the looks of surprise on the faces of people who recognized him.

And yes, here’s the thing … I AM proud AND humbled to have followed in his footsteps, even if I was basically left with no choice but to and even if most of the trails I trekked mostly diverged from his, mainly to his chagrin and my secret delight.

For life, for the memories, for the journalism, for the grit, for the stubborn sense of integrity, damn it, even for – well everyone says so, so I guess it must be true – this face, thanks Dad. See you around!

READ ALSO:

Journalist Rolando “Rolly” Espina, 84