This article is part of the Reuters series, ‘The Body Trade’.

PHOENIX — Sam Kazemi stood over the old man’s corpse. Nearby lay pliers, a scalpel and a motorized saw designed to cut drywall and pipe.

On a busy day, Kazemi might harvest body parts from five or six people who had donated their bodies to science. On this day in November 2013, the corpse before Kazemi typified the donors who gave their remains to his employer, Biological Resource Center.

The man was a retired factory worker with a ninth-grade education. He had lived with his wife in a mobile home in Mohave Valley, Arizona, and had died six days earlier, aged 75. His name was Conrad Patrick.

But after he died and his body was donated, Patrick became a commodity, known by the company’s initials and a number: BRC13112103.

Reuters reviewed thousands of internal BRC records and confidential law enforcement documents containing profiles of Patrick and 2,280 other donors. The documents include invoices and inventories for thousands of body parts harvested from those people. They show how their bodies were dissected, which body parts were sent where, and why buyers obtained them.

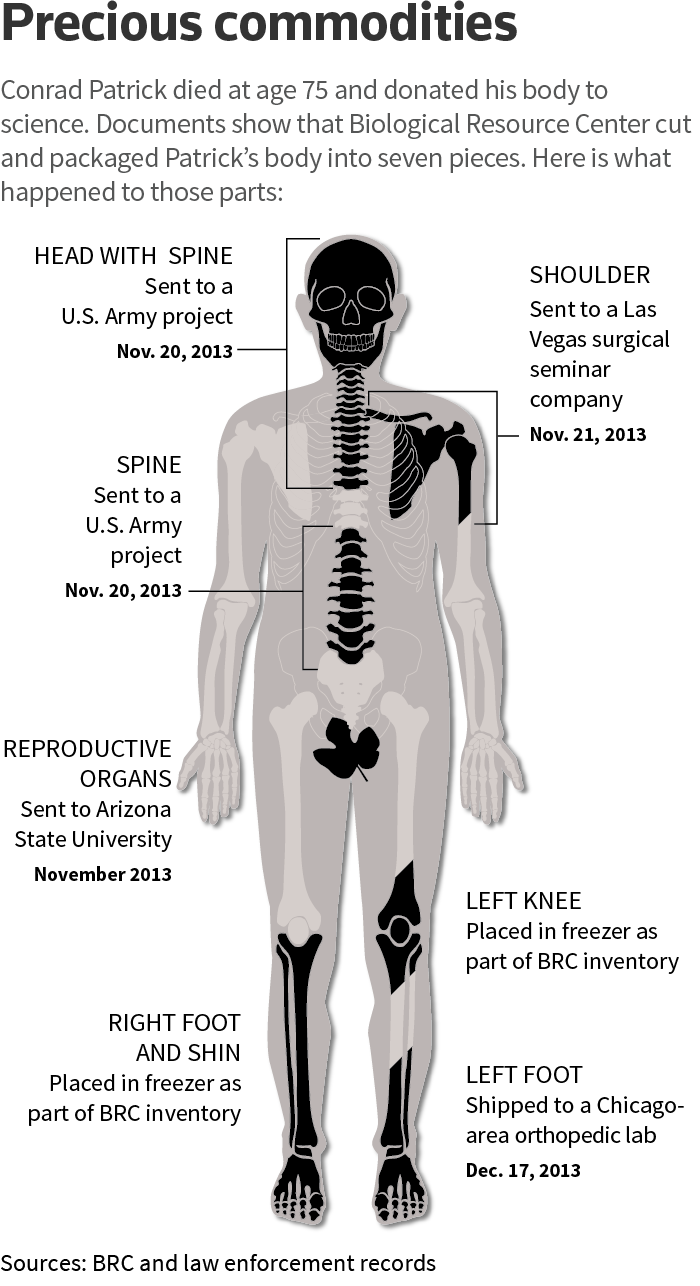

Kazemi helped cut up and package Patrick into seven pieces. BRC shipped Patrick’s left foot to a Chicago-area orthopedic lab. His left shoulder was sent to a Las Vegas company that holds surgical seminars. His head and his spine went to a project run by the U.S. Army. And Patrick’s “external reproductive organs” were sent to a local university. His right foot and left knee were placed in the company’s freezers, where they became part of BRC’s million-dollar inventory of flesh and bone.

For more than a year, Reuters has examined America’s body trade, a little-known and virtually unregulated industry. These businesses, which call themselves non-transplant tissue banks, are also known as body brokers.

The operations can resemble meat-packing plants. At BRC, body parts from heads to fingernails were harvested and sold. On Saturday mornings, Kazemi taught college students how to dismember cadavers in the company lab. He also starred in a grisly training video, demonstrating how to carve out a man’s spine using a motorized saw.

The documents obtained by Reuters — along with dozens of interviews with investigators, former BRC workers and families of donors — offer an unparalleled look at how one of America’s major body brokers operated.

The records, never before made public, also reveal how little the government or the donors themselves understood what was happening at the company, and show in graphic detail how a cadaver becomes a commodity.

Sales invoices detail many of those transactions.

For $607, BRC sold the liver of a public school janitor to a medical-device company. The torso of a retired bank manager, bought by a Swiss research institute, fetched $3,191. A large Midwestern healthcare system paid $65 for two femoral arteries, one from a church minister. And the lower legs of a union activist were purchased by a Minnesota product-development company for $350 each.

For raw material, the industry relies in large part on people too poor to afford a funeral, offering to cremate a portion of each donated body for free.

A Reuters analysis of BRC donor files from May 3, 2011 through January 20, 2014 confirmed how important the disadvantaged were to business. The vast majority of BRC donors came from neighborhoods where the median household income fell below the state average. Four out of five donors didn’t graduate from college, about twice the ratio of the country as a whole.

Before brokers accept a body, they typically present the donor or next of kin with a consent form. These agreements are often written in technical language that many donors and relatives say they find hard to understand. The documents give brokers the right to dismember the dead, then sell or rent body parts to medical researchers and educators, often for hundreds or thousands of dollars. At BRC, a whole body sold for $5,893, records show.

Since 2004, when a federal health panel unsuccessfully called on the U.S. government to regulate the industry, Reuters found that more than 2,357 body parts obtained by brokers from at least 1,638 people have ended up misused, abused or desecrated.

Documents reviewed for this article indicate that those figures are vastly understated. The extent of BRC’s operation surprised even investigators who raided the Phoenix-based company in 2014.

There, agents discovered 10 tons of frozen human remains — 1,755 total body parts that included 281 heads, 241 shoulders, 337 legs and 97 spines.

Applying a state forfeiture law, authorities hauled away the contents of BRC’s freezers, filling 142 body bags. One bag held parts from at least 36 different people.

The seizure was so large that officials struggled to properly handle the body parts. When plans to cremate the remains stalled, officials brought three walk-in freezers to a military base and stacked the body bags inside, one atop another. Parts from 851 different people remained in those freezers for almost three years before they were cremated.

The raid on BRC was part of a broader federal probe into the suspected practices of one of its clients, Arthur Rathburn. A Detroit body broker, Rathburn has pleaded not guilty to charges of defrauding customers. During a 2013 search of Rathburn’s warehouse, federal agents found rotting body parts along with four preserved fetuses, confidential photographs reviewed by Reuters show. It is not clear how Rathburn acquired the fetuses or what he planned to do with them. He was indicted for allegedly selling diseased body parts without warning buyers. His trial is set for January.

After the BRC raid, the company went out of business. Its founder and former owner, Stephen Gore, later pleaded guilty to fraud — not for selling body parts but for misleading customers by shipping them contaminated specimens. His punishment: probation. He is expected to testify at the Rathburn trial.

Gore’s attorney, Clark Derrick, said Gore always tried to act in the best interests of his donors. “At some point the business grew exponentially, we became shorthanded, we cut some corners, and for that I apologize and make amends,” Derrick said on Gore’s behalf.

Profiting off the poor

Gore housed his business in a 9,000-square-foot building once occupied by an insurance agency — a one-story facility near two interstate highways and the Phoenix airport. From 2005 until early 2014, court records show, BRC received about 5,000 human bodies and distributed more than 20,000 body parts.

As Reuters reported last year, BRC also sold body parts to U.S. Army contractors for military experiments. A Pentagon spokeswoman said BRC provided the body parts “under false pretenses,” misleading the Army that consent had been secured for donors to be used in destructive tests.

Among the parts BRC sold for the Army experiments were the heads and spines of Conrad Patrick and Leon Small, a 71-year-old retiree who had once managed a furniture factory.

On the consent forms Patrick and Small signed, each man checked a box stating that he did not wish to be used in military or destructive tests, records show.

But just days after Patrick and Small died, a BRC employee called their widows and persuaded them to amend the forms so their husbands could be used by the military, according to recordings of the calls reviewed by Reuters. The widows said the calls came during a traumatic time.

“I didn’t understand what they were talking about,” Dona Patrick said. “But I said ‘OK.’”

Bodies or parts from at least 20 BRC donors were used without their consent in Army experiments, Reuters found. Parts from Small and Patrick, however, were not. The military halted testing when it learned of the raid at BRC.

The shoulders of both men were sent to a for-profit surgical training company in Nevada.

The widows, Karen Small and Dona Patrick, are among two dozen next of kin who said they were surprised to learn that BRC profited from a relative’s donated body.

“They prey on people that have no money, that are poor, that have no insurance — like us,” Patrick said.

Family members of some donors said BRC employees led them to believe body donation was regulated by federal and state authorities, and that selling body parts is illegal. Based on those pitches, the relatives said they believed the remains wouldn’t be sold. In truth, there are virtually no regulations on the body trade

“It’s a horrible thing,” Small said. “Sick.”

In a statement to Reuters last year, Gore said his employees took “great care to ensure that donors and their families were well-informed about the processes.” Gore acknowledged at his sentencing that he relied on books and the Internet for instruction on how to handle the bodies he sold.

‘Homemade horror movie’

In 2012, BRC hired lab technician Kazemi. He earned $21 an hour. Before joining the company, his resume shows, he spent the previous decade working as a real estate agent, a waiter at a Morton’s steakhouse and a manager for an Olive Garden restaurant.

When he arrived at BRC, he was 35 and had just graduated from Arizona State University with a degree in kinesiology, the study of body movement. At ASU, he was a teaching assistant in an anatomy lab.

In 2013, Kazemi starred in a BRC instructional video. It opens with a jarring title, punctuated for emphasis: “Stripped Cervical Spine!”

The video begins with a close-up of Kazemi wearing a mask, gloves, goggles and a surgical gown. Then it pulls back to reveal a body face down on a table. The man’s shoulders and arms have already been sheared off. The head lolls from side to side until Kazemi holds it still.

With a scalpel, he makes incisions along the neck and back, then peels away the man’s skin and scalp. About seven minutes into the video, Kazemi picks up a construction saw.

“On this one,” he says of the cadaver, “we are using a sturdy, thicker 9-inch blade. You want to make sure that the blade is long enough to reach from ear to ear across the back.”

In his interview with Reuters, Kazemi described the video as clinical and “not disrespectful to donors” in any way. It was meant for internal use only, he said. Kazemi also said he did not know how BRC acquired donors or where body parts were shipped.

In hindsight, Kazemi said using a motorized saw was wrong because it cannot be cleaned well enough to avoid spreading diseases.

“Would I do something like that now that I know better? No,” Kazemi said. “But at the time, that’s what was provided to me.”

Two retired investigators for the Arizona attorney general said even veteran prosecutors recoiled when they viewed the 24-minute video.

“It was like a homemade horror movie,” said Charles Loftus, the former assistant chief agent.

“I couldn’t sleep at night after seeing that,” said Matthew Parker, another former agent who says he retired with a disability – post-traumatic stress disorder – related to his work on the case. “It looked like a junkyard chop shop where they are just ripping things apart.”

Interning at BRC

Kazemi also spent Saturdays in BRC’s lab teaching college students about dissection.

On one Saturday in late 2013, ASU junior Emily Glynn said she showed up for her first day at the lab. She was majoring in nutrition.

“I was really surprised when I got the internship because I didn’t have any experience,” said Glynn, then 20. “Just went in the first day and learned things on the job.”

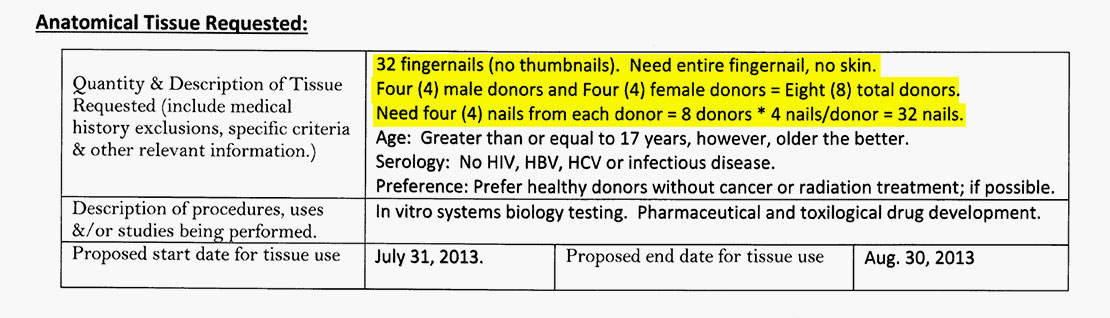

That first day, under Kazemi’s direction, interns used pliers to remove fingernails from donors, Glynn recalled.

“I don’t want to say it was barbaric, but it was weird,” she said. “One day, I found myself holding the hand of a 70-year-old woman and felt like I needed to apologize to her, to say, ‘I’m sorry.’”

Neither Glynn nor Kazemi knew how the fingernails were used, they said, and Reuters could not locate invoices for that order. But the news agency did identify fingernails from 22 other donors that were sold by BRC. They went to a North Carolina bioengineering research company, SciKon Innovation.

SciKon CEO Randy McClelland said he was unaware that BRC was raided by the FBI. He said his business helps companies study how products enter the bloodstream through fingernails. “Like new cosmetics that go on your skin,” he said.

On another Saturday, Glynn said, Kazemi gathered the interns around the body of another elderly woman.

“He says, ‘Emily, you’ve never cut off a head before, and everyone else has, so do you want to try?’” Glynn recalled. “And I’m, like, ‘OK.’”

As she held the reciprocating saw, Glynn said, Kazemi steadied her grip.

“It wasn’t a full-on chainsaw like you would see in a horror movie, but it was a smaller version,” Glynn said. “And then I just went for it. I was expecting lots of blood but there wasn’t much to it. It came right off,” she said of the woman’s head.

Kazemi said he doesn’t remember helping an intern cut off a head or any other body parts. The Saturday sessions, he said, were more akin to lectures during which he showed interns various organs and other body parts.

In her senior thesis, Glynn described her time at BRC differently.

“Over the course of the internship, I stripped subcutaneous fat from the vertebrae of a cervical spine, practiced performing cricothyrotomies (incisions to the throat), sutured dismembered legs using an oversized needle and twine, and decapitated an elderly woman with what looked and sounded like a chainsaw from Home Depot,” Glynn wrote in her thesis. “Not once did I receive formal training or instruction.”

Body parts to middlemen

BRC’s customers were not always directly acquiring body parts from the broker for their own medical education, research or training programs. According to invoices, some customers were middlemen – brokers who resold or leased body parts originally donated to BRC. The consent forms gave BRC the discretion to choose its customers, but the forms did not state that body parts could be resold by third parties.

In 2012 and 2013, BRC sold at least 961 body parts, including at least 224 human heads, to three such middlemen.

One was Innoved Institute LLC, a Chicago-area medical lab provider that also supplies human body parts. Innoved was among BRC’s best customers. It received at least 32 shipments with 277 body parts. Innoved executives did not respond to requests for comment.

Another was Rathburn, the Detroit-area broker facing trial next month. He received at least 26 heads from BRC. Rathburn’s lawyers did not respond to a request for comment.

A third middleman was Biological Resource Center of Illinois, another Chicago-area broker. Better known as BRC-IL, it received at least 658 body parts from BRC. BRC-IL operated independently from BRC. But it was also raided by FBI agents as part of the federal probe into suspected fraud against donors and customers. No one has been charged with a crime in the BRC-IL matter, and executives there did not respond to requests for comment.

One of the shoulders shipped to BRC-IL came from the body of Robert Louis DeRosier, a casino security employee. He died at age 64 after a long battle with diabetes.

His widow, Tama DeRosier, lives in a mobile home park in Mohave Valley, Arizona. She said her husband donated his body hoping it might contribute to diabetes research. She did not expect anyone to make money selling his remains.

“That’s morbid,” the widow said. “Greed is a terrible thing.”

Russell Parker Jr, who helped care for his dying brother Todd, said he was surprised to learn from a reporter that BRC sold Todd’s right knee and offered to sell Todd’s head. Friends had recommended BRC, he said. And when the company returned his brother’s ashes, everything seemed “all on the up and up, very professional.”

“Shame on BRC for showing such disrespect,” Parker said. “That’s so wrong. It’s like trafficking.”

Confused consent

The companion of one donor cited another area of confusion: BRC’s use of the term “tissue.”

In sales pitches and on consent forms, body brokers commonly talk about retrieving tissue from donors. To the medical community, “tissue” means any part of the body — from an organ to a torso.

But in interviews with Reuters, family members of some donors said they believed “tissue” meant only skin samples. Though BRC did sell skin, those sales represented just 2 percent of its business, invoices show.

Maureen Krueger said her partner of 42 years, Fidel Silva, told a female hospice worker in his final days that he wished to be cremated.

“And that’s when she brought it up: ‘Would you be interested in donating tissues?’” Krueger recalled.

The way she understood it, Krueger said, a few skin samples would be removed for research purposes. In return, BRC would cremate Silva for free. Silva, a 69-year-old construction worker with a high school degree, peppered the hospice worker with questions.

“He asked, ‘Well, are you sure? What are they going to do?’” Krueger said. “He wanted to know. And that’s when she assured him it was only body tissues, they only took samples, they didn’t remove any organs or parts or anything. It was just tissues. And that’s when Fidel agreed.”

The conversation took place at the Hospice of Havasu in Arizona. Its executive director, Dan Mathews, said he could not discuss the matter due to patient-privacy laws. But he said the hospice, which offers its clients options to donate their bodies to science, “removed that company BRC from our list of providers” upon hearing it was under investigation.

Internal BRC records show the body broker removed Silva’s head, and his right and left arms from shoulder to hand. Each was tagged with a tracking number and prepped for sale.

“Wow,” Krueger said. “I didn’t really realize they could do all that. I mean, I didn’t understand that’s what would happen with Fidel at all.”

Body parts in limbo

After the raid of BRC by federal and state agents, the body parts seized by authorities remained in limbo for almost three years. Their fate, detailed in confidential state logs, sworn statements and photographs, has never been made public.

Logistical problems began the day of the raid, said former agents Parker and Loftus. Authorities were stunned to find so much human flesh inside BRC, they said.

“We expected two freezers and a few hundred pounds of body parts,” said Loftus, who’s now running for state representative. “Instead, we found 40 freezers with 10 tons of bodies and parts.”

Agents entered in hazmat gear and took biopsies from each body part to preserve as evidence. Records show the agents then placed the 1,755 parts into 142 body bags.

The bags were sent to 10 local funeral homes so the remains could be cremated. But records and interviews show that BRC and others for whom it was storing body parts objected to their destruction. They argued that the parts had a value of more than $1 million.

The cremation plans were put on hold, but authorities soon faced a pressing problem, according to former agents Loftus and Parker. Funeral homes could refrigerate but not freeze the body parts, and the mortuaries began to complain that some of the parts were starting to thaw.

As a solution, authorities obtained three walk-in industrial freezers and installed them at a military base used by the Arizona National Guard. Then, body bag by body bag, the mortuaries delivered the parts, and Loftus and Parker helped carry them into the freezers.

In an interview, Parker recalled feeling body parts sloshing around inside the bags as he moved them. Some bags leaked blood that stained his pants and shoes. The experience led to his PTSD diagnosis, he said.

“It’s not how you treat human beings, human remains,” Parker testified in a deposition as part of his PTSD claim. “You don’t throw them in a bunch of body bags and then throw them into a freezer like a pile of garbage.”

The spokeswoman for the Arizona Attorney General’s Office said the body parts were kept for federal authorities “as evidence in ongoing criminal investigations and prosecutions across the country.” An FBI spokesman declined to comment. In February, after almost three years in the containers, the remains were cremated and returned to families that requested them, the state spokeswoman said.

In response to the Gore case, the Arizona governor signed into law a bill that requires body brokers like BRC to be licensed and regularly inspected. The new law calls for brokers to follow a set of standards and to hire a medical doctor to supervise company practices.

Although the law was adopted a year and a half ago, it has yet to be enforced: The state health department still must create specific rules for brokers. It isn’t clear when it will. Health department officials, said a spokeswoman, “do not have an anticipated date of completion at this time.”