On an icy December day in 2011, North Korea’s new leader Kim Jong Un was accompanied by seven advisers as they escorted the hearse that carried his father, Kim Jong Il, through the streets of Pyongyang.

None of the men remain with the young Kim. This October, he demoted the last of his father’s aides, both men in their nineties. They were among around 340 people he has purged or executed, according to the Institute for National Security Strategy, a think tank of South Korea’s National Intelligence Service.

Kim, “obviously a madman” in the eyes of U.S. President Donald Trump, has completed a six-year transition to what the South calls a reign of terror. His unpredictability and belligerence have instilled fear worldwide: After he tested a “breakthrough” missile earlier this week, he pronounced North Korea a nuclear power capable of striking the United States. But a closer look at his leadership reveals a method behind the “madness.”

At 33, Kim Jong Un is one of the world’s youngest heads of state. He inherited a nation with a proud history, onto which a socialist state had essentially been grafted by Cold War superpowers to create a buffer between Communist China and the capitalist South. Under Kim’s father, the economy was mismanaged, and the collapse of Communism in the Soviet Union eliminated an important source of support. Up to three million people starved.

Lee, a leading North Korea leadership researcher, said the state’s theory of succession means Kim the younger’s rise should have been completed while his father was alive: Kim’s father was anointed 20 years before he took over, giving him time to build allies and a leadership system.

Kim Jong Un had just three years as leader-in-waiting.

Born in 1984, he was third in line for power and a fractious, competitive child, according to Kenji Fujimoto, a Japanese chef who worked for the family and one of the few people to recount meetings with the young Kim.

In his memoirs published in 2010, Fujimoto, who now runs a sushi restaurant in Pyongyang, said Kim once snapped at his aunt Ko Yong Suk for calling him “Little General.” Kim wanted to be called “Comrade General.”

When Kim Jong Il knew his young son would soon succeed him, researchers have said, the father took several measures to protect the boy. Lee said these included shifting the country’s power base to create rivalry between the elites so Kim the younger could play one group off against another.

Kim Jong Il had declared the military the country’s supreme power — a policy known as songun, which means “military first.” At a party conference in 2010, he changed the setup so the military had to compete with the party administration for the leader’s favor.

‘Poor man’s weapon’

Military strategy was the first thing Kim changed. His father had used the promise of nuclear disarmament as a bargaining chip for aid, and in February 2012, young Kim started in his father’s footsteps, promising to freeze North Korea’s nuclear program in return for food aid from the United States.

But weeks later he changed tack, saying North Korea would fire a long-range rocket.

“The negotiations were carried on as the legacy of Kim Jong Il,” said Wi Sung-lac, a former South Korean envoy to talks in 2011 that contributed to the February deal. “Since then his strategic thinking has shaped up.”

In Kim’s view, Saddam Hussein of Iraq and Muammar Gaddafi of Libya were fatally weakened by not having nuclear weapons, North Korean media say. “History proves that powerful nuclear deterrence serves as the strongest treasured sword for frustrating outsiders’ aggression,” the official KCNA news agency said in an editorial in January 2016.

North Korea is racing to achieve a nuclear deterrent because the state feels threatened, worrying particularly that Kim may face a fate like Gaddafi. The Libyan leader agreed in 2003 to eliminate his weapons of mass destruction; in 2011, he was killed by rebels that the United States and its allies had supported.

Months after Kim’s accession, North Korea updated its constitution to declare itself a nuclear weapons state.

One leading pallbearer at Kim Jong Il’s funeral was Ri Yong Ho, Chief of the General Staff of the Korean People’s Army. Kim sacked him in July 2012. South Korean intelligence later confirmed that Ri had been executed.

By December 2012, North Korea had carried out another, successful, rocket test.

In 2013, Kim outlined a new policy: The “byungjin line,” or parallel development, to combine the nuclear buildup and economic growth.

A nuclear deterrent is essential to that, says Thae Yong-ho, North Korea’s former deputy ambassador to London, who staged a high-profile defection to South Korea in 2016. The threat of absolute destruction makes a nuclear bomb a “poor man’s weapon” with which to tighten control of the country and ensure long-term rule, Thae said.

“Once he has assumed control of usable nuclear weapons, he has more room to allocate resources more flexibly, and allocate the military forces for civilian construction,” said Thae.

‘Foolish dream’

North Korea spends about a quarter of its GDP on defense: Russia’s President Vladimir Putin has said Kim Jong Un would have his people “eat grass” rather than give up its nuclear program.

But with a legacy of famine, Kim also says he wants to boost people’s prosperity.

The former chef, Fujimoto, said that on one summer break from school in Switzerland in 2000, the young Kim was preoccupied with a visit to Beijing his father had made.

“Let’s talk,” Fujimoto recalled the future leader saying over drinks on his father’s private train. “I hear from higher up that China seems to be succeeding on many fronts — engineering, commerce, hotels, agriculture — everything,” Kim said. “In many ways, don’t we need to take them as a model example for us?”

In 2012, shortly after taking power, Kim went a small way to mimic reforms China made in the 1980s. Farmers were allowed to keep most of the harvest. State enterprises were given the right to buy and sell at market prices and to hire and fire workers. Private entrepreneurs and traders were encouraged to invest in state projects or with party and military entities. Kim also began to turn a blind eye to informal markets — a force his father tried in vain to contain.

That April, Kim addressed the nation — the first time in 17 years North Koreans had heard the voice of their leader. “It is the party’s steadfast determination to ensure that the people will never have to tighten their belt again,” he said.

Outsiders hoped the reform signaled a new political openness as Kim drove to promote the North in the world: In 2012 Antonio Razzi, an Italian senator for Forza Italia who calls himself the only Italian to have met the leader, said Kim had asked him to find training facilities for soccer players in Italy.

“I have talked with many (North Korean) local leaders,” Razzi said. “They have no plan to attack anybody. North Korea is interested in nuclear only as a form of defense.”

Kim worked to ensure the economic freedom would not unseat him.

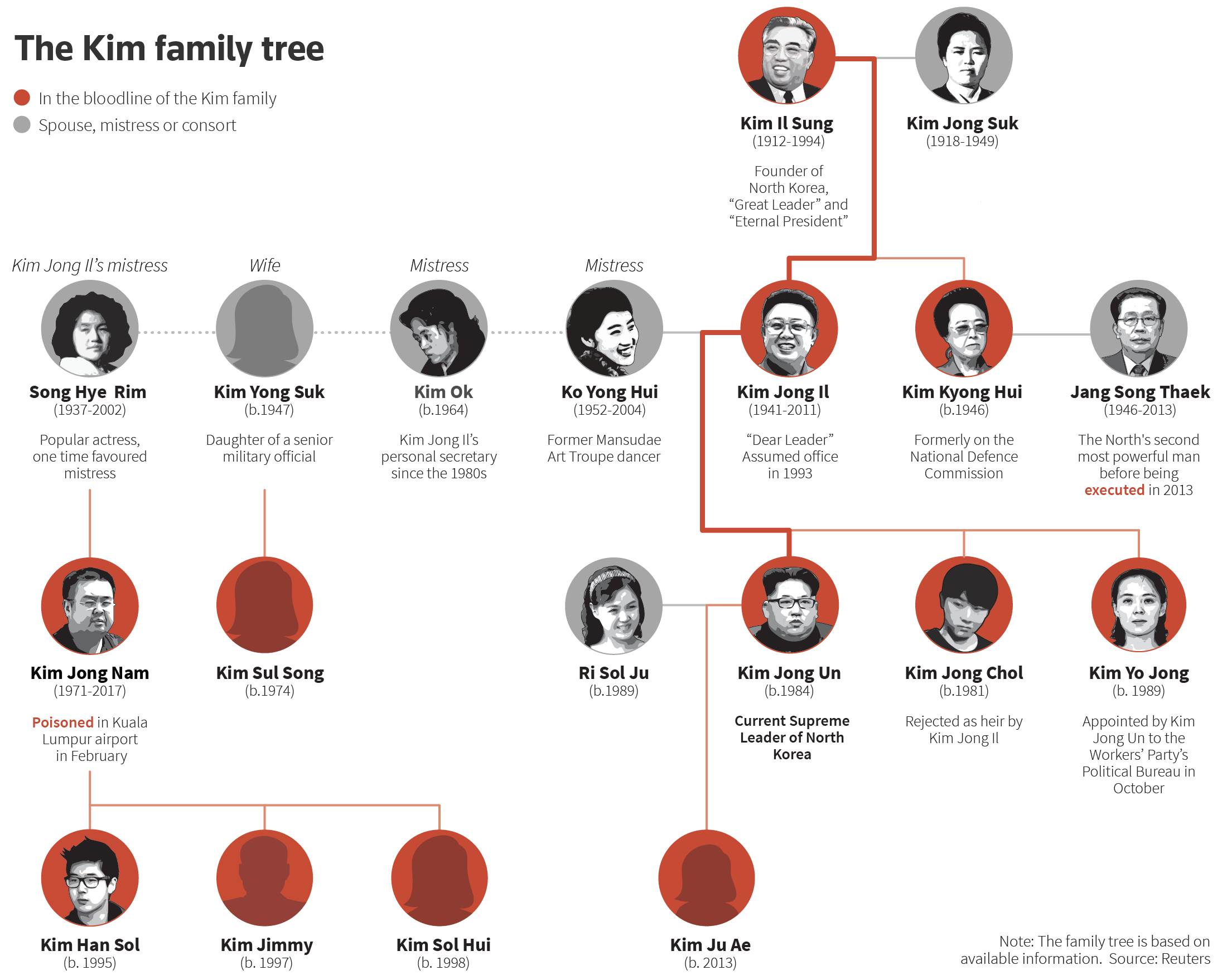

Also escorting his father’s funeral car in 2011 was Jang Song Thaek, an administrator at the vanguard of the reforms. He was married to Kim Jong Il’s sister, was a special envoy to China and had overseen a host of new Special Economic Zones all over the country.

In December 2013, Jang was hauled out of the Politburo in front of the cameras and accused of plotting a coup. “Jang dreamed such a foolish dream,” state media said, adding Jang hoped his reformist plans would help him “get ‘recognized’ by foreign countries.”

Jang was shot “dozens of times” by an anti-aircraft gun and his remains removed with a flamethrower, according to South Korea’s National Intelligence Service — an account no one has confirmed.

‘Development dictator’

From that point on, Kim honed his personality cult. On the day Jang’s purge was announced, North Korea’s official daily the Rodong Sinmun unveiled a song dedicated to Kim Jong Un, titled “We Know Nothing But You.” More were to follow.

The next year, Kim also ordered school textbooks be revised to focus on idolization of himself and include images of nuclear weapons and missiles, according to the NIS-affiliated Institute for National Security Strategy.

The idolization campaign kicked into high gear in 2016, focused on pop culture and youth: Kim’s chosen female singers, the Moranbong Band, staged a series of musical performances and plays calling for loyalty to the leader, while the Shock Brigade, a crew of young North Koreans in charge of major economic construction, produced about 1,200 poems and other literary works, the Institute said.

“He has linked his own legitimacy to improving the economic situation in the country,” said John Delury of Seoul’s Yonsei University. “Kim Jong Un wants to become a development dictator.”

At home, he casts himself as a bringer of plenty. In 2015, almost half the times he was photographed were at economic events, data from Seoul’s Unification Ministry shows. Only this year, as his weapons tests multiplied and met an angry response in the United States, have military appearances come back into prominence.

Standing tearfully behind Kim Jong Un at their father’s funeral was his younger sister, 28-year-old Kim Yo Jong. On the same October day that Kim dropped the last two of his father’s aides, he included her in his Politburo. Kim Jong Chol, their elder brother, leads a quiet life in Pyongyang where he plays guitar in a band, according to former ambassador Thae.

“I think Kim Jong Un has been making good use of the existing system, while strengthening his power base and dictator regime in a very shrewd manner,” said Lee Su-seok, a research fellow at the Institute for National Security Strategy.