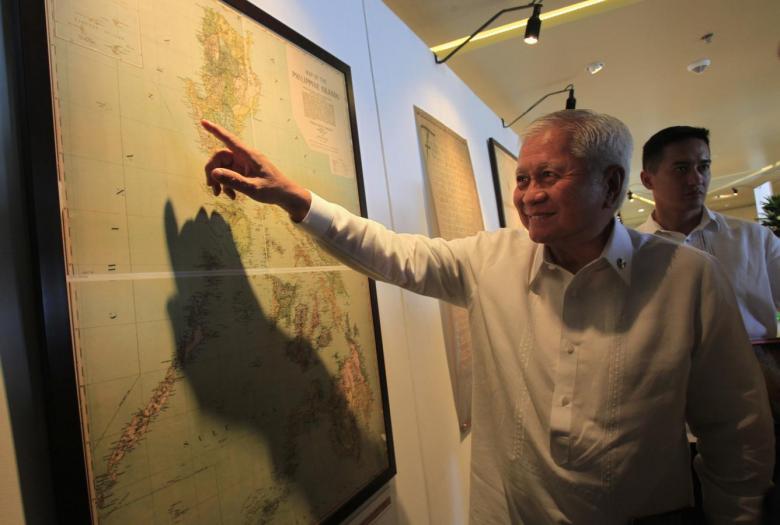

MANILA, Philippines — Former Foreign Affairs Secretary Albert del Rosario has floated the idea of a “strategic build-up of defense capabilities for deterrence purposes” in dealing with the dispute in the South China Sea, even as he stressed that adherence to international law is the best way to “safeguard peace and stability.”

At the “ASEAN Leadership Amid a New World Order” hosted by the Stratbase Albert del Rosario Institute-at the Makati Shangri-La on Wednesday, November 8, Del Rosario read a letter he had written to the leaders of the Philippines, other Association of Southeast Asian Nations member-states, China, the United States, and “other concerned nations.”

In the letter, he said if trying to get these countries to adhere to the rule of law does not work, an alternative is “an approach characterized by a strategic build-up of defense capabilities for deterrence purposes.”

Del Rosario referred to experts who suggest that Southeast Asian countries “thoughtfully ramp up their defense transfers and invest in select military platforms as a matter of necessity.”

“Although a cycle of reactive militarization will surely raise the stakes and the tension, this may still be a prudent path,” he said. “In the words of a U.S.-China relations expert, Ely Ratner, ‘Beijing will not compromise as long as it finds itself pushing on an open door’.”

Del Rosario noted that countries concerned about developments in the South China Sea have a common purpose: “to ensure the peace, prosperity, and stability of this region.”

At the same time, they are facing serious issues such as “the continued testing of nuclear capabilities on the Korean Peninsula and the ongoing challenges in the South China Sea.”

Resolving these, he said, “will require the full strength of our cooperative abilities, not our coercive ones.”

More than seeking to achieve “temporary advancements of our respective national interests,” Del Rosario asked the leaders to also think about the goal of long-term peace, security, and prosperity of the region.

“What order should we be pursuing for this region? What sustainable arrangement among our states ensures not only the absence of war, but also an encouraging environment of trust and confidence?” he asked.

“When all of us agree to rules and commit to upholding them, together we create predictability, foster an environment conducive to resolving disputes, and maintain the dignity of our independence and sovereign equality as nations,” he said.

“Adherence to international law is moreover the root of order and stability in our inter-state relations. By promoting and adhering to the law, each of us are safeguarding peace and stability,” he added.

He warned that veering from the law has led to “a disjointed reality between the statements that we make and the practices that prevail on the ground” and pointed out tha militarization, in particular, sows distrust.

“China has used a creeping force to ensure its control of the vital waterways on which we all depend,” Del Rosario pointed out. “The Philippines and others in the region have spoken out repeatedly against actions that we know to be contradictory to China’s commitments, whether to the letter of the law or its spirit.”

He urged the Asian behemoth to “consider if, in achieving its present military or economic objectives, it will continue to have a measure of respect from its neighbors …,” but added this would only be “possible if China pursues its aims within the framework of international law.”

“We know that it can do so, because China’s path to ascendance as a nation has not always been led by its might,” he added.

He also urged a return to a time “not too long ago that our seas were less tumultuous and our differences were less intractable,” warning that “time is running short for us to return to that period.”

READ DEL ROSARIO’S LETTER:

To the leaders of the Philippines, other ASEAN nations, China, the United States, and other concerned nations:

Our common purpose is to ensure the peace, prosperity, and stability of this region. As you know, over 600 million people call Southeast Asia home. The region is not only one of the world’s largest population centers, it is host to several of its youngest, fastest-growing, and most dynamic economies.

The region has many factors working in its favor. At the same time, it has serious problems to face. The fates of the Southeast Asian nations and our primary trade and security partners are becoming more intertwined. Financial problems in one country may ricochet on another, just as security concerns in one area can engulf others.

Many recent developments are of grave concern. There are the continued testing of nuclear capabilities on the Korean Peninsula and the ongoing challenges in the South China Sea, both of which are foremost issues. The resolution of these matters will require the full strength of our cooperative abilities, not our coercive ones.

We have a long way to go in achieving the success that we seek. In the case of the United States, which had taken on the banner of promoting the rule of international law, the ‘Asia Pivot’ was, unfortunately, not a focused one. The US had communicated its desired outcomes with too few reassurances for its partners in this cause. Today, its approach to Asia thus far does not yet appear to be dominated by support to the institutions it helped build and to the values it helped foster.

Nevertheless, it is our hope that the United States’ support in our region will sooner than later be concretized.

In the case of China, its internal motivations have set it in the direction of expansion. While undertaking its expansionary goals, specifically in the South China Sea, China has not upheld its legal obligations and diplomatic commitments to this region, nor acted with due respect for the clearly established rights of its neighbors.

While we are seeing the signs of continuity in its leaders, I would like to believe that China is still at a crossroads. It can still decide whether or not the benefits of its muscular approach outweigh the detriments to the whole of our neighborhood.

I turn now to ASEAN. The bright promise of Southeast Asia’s future contrasts against the fog of the present. In the midst of many changes in our environment, many of our states have found themselves being pulled in different directions. This has been worsened by a lack of leadership from among us. In broader context, one can say that ASEAN is adrift.

ASEAN is striving to be a rules-based community, to strengthen its centrality, and to more actively contribute to the stability of the Asia-Pacific. As an institution, it provides a platform for us to present and reconcile our interests and manage our differences. However, the trust that we can place in ASEAN is not immovable; this trust depends on the body’s ability to achieve meaningful consensus and demonstrate its effectiveness.

If ASEAN pursues an over-abundance of caution, it risks becoming only a bystander to the events within its own region.

The Philippines is still finding its way in this new environment. Still, we have taken a few sure steps. We did what we could toward ensuring the peaceful settlement of our disputes in the South China Sea. The region has benefited from the clarity of the international tribunal’s decision, whose reasoning also applies to the complaints of our neighboring states. The outcome of the case is final and will stand through time.

Our call for adherence to international law was shared by other concerned states, who appreciated the tribunal’s ruling as not only an important moment for one country but also a service to the whole of the region. These states, such as Japan and Australia, have repeatedly affirmed the significance of the ruling and of international law to the conduct of countries’ relations in the Asia-Pacific region.

As the leaders of these countries being respectfully addressed, I believe that you are not only well versed with what I have just described, you are also thinking carefully about what path your countries will travel. At this juncture, the state of our international environment calls for our leaders to make an honest self-examination.

In our view, such an examination should not only be seen against the goal of achieving temporary advancements of our respective national interests, but also the long-term peace, security, and prosperity of our region. From where each of us stand, we must ask: What order should we be pursuing for this region? What sustainable arrangement among our states ensures not only the absence of war, but also an encouraging environment of trust and confidence?

Perhaps you already have some idea of my answer. I have previously said that Philippine interests are best promoted when all states, of any size or power, adhere to the commonly-agreed upon standards that govern countries’ rights and responsibilities. Through international law, a country of 100 million people is the equal of another more than ten times its size. In no other arena would we have the same footing.

While I have said this for the Philippines, I believe that the appeal of adhering to international law applies to all of the concerned states in our region. When all of us agree to rules and commit to upholding them, together we create predictability, foster an environment conducive to resolving disputes, and maintain the dignity of our independence and sovereign equality as nations.

Adherence to international law is moreover the root of order and stability in our inter-state relations. By promoting and adhering to the law, each of us are safeguarding peace and stability.

I would like to take a further step and suggest that the challenges that we presently face may be attributed to a lack of emphasis on the importance of international law. Without this emphasis, we have a disjointed reality between the statements that we make and the practices that prevail on the ground. These practices, with militarization chiefly among them, add to confusion and subtract from enduring trust.

The farthest alternative to our system of rules is a system of pure dominance, using a combination of economic and military means. The annals of world history have shown us that this arrangement is not sustainable, and that it persists only until the balance of power changes again.

What is needed, therefore, is less resort to coercion and brute strength and greater resort to the paths that are not only peaceful, but acceptable and legitimate to all.

This perspective applies directly onto the issue of the South China Sea. China has used a creeping force to ensure its control of the vital waterways on which we all depend. The Philippines and others in the region have spoken out repeatedly against actions that we know to be contradictory to China’s commitments, whether to the letter of the law or its spirit. Last year, as you know, a neutral tribunal of international legal experts vindicated this view in the decision that was handed down to us and welcomed by many in this region and in others beyond it.

In our view, China should consider if, in achieving its present military or economic objectives, it will continue to have a measure of respect from its neighbors. In my view, this is only possible if China pursues its aims within the framework of international law. We know that it can do so, because China’s path to ascendance as a nation has not always been led by its might.

Yet, if trying to get everyone to adhere to the rule of law does not work, one other alternative is an approach characterized by a strategic build-up of defense capabilities for deterrence purposes. Some experts have suggested that the countries of the region should thoughtfully ramp up their defense transfers and invest in select military platforms as a matter of necessity. Although a cycle of reactive militarization will surely raise the stakes and the tension, this may still be a prudent path. In the words of a US-China relations expert, Ely Ratner, “Beijing will not compromise as long as it finds itself pushing on an open door.”

The least desirable option is sheer capitulation: for us, smaller states especially, to give in and to lose our sovereign equality and all that it signifies. This is not a win-win solution, only a guarantee that we bequeath our grievances to our children. This option is totally unsatisfactory.

To the leaders I have mentioned: It was not too long ago that our seas were less tumultuous and our differences were less intractable. Time is running short for us to return to that period.

With the cooperation and goodwill of all relevant states, however, and their sincere commitment to the principles of international law, perhaps the peace, stability, and prosperity of our region could still prevail.

To benefit all, it behooves us to work together in upholding that right, instead of might, should be our guiding principle.

Sincerely,

Ambassador Albert Del Rosario

Chairman

Stratbase ADR Institute