Jimmy (not his real name), 36, had saved up for eight years to apply for a job overseas.

A resident of Bacolod City, he worked as a car salesman earning P14,000 (US$280) monthly. But as his family’s needs grew, he realized he needed a job that paid better and saw working abroad as the solution.

In 2011, he applied through a recruitment agency to be a driver in Doha, Qatar with a promised monthly salary of P30,000 ($600), more than twice what he was earning in Bacolod. But first he had to pay the agency a placement fee of P20,000 ($400).

In all, he shelled out a total of P60,000 ($1,200) in recruitment and other related fees, wiping out his family’s savings.

After five years working in Qatar, Jerry decided he needed to earn more. His children were growing up fast, there were more bills to be paid, and he saved nothing of his monthly salary, dutifully sending everything to his wife.

A coworker told Jimmy he planned to apply as a driver in New Zealand where they could supposedly earn $2,000 (P100,000) a month, more than thrice their pay in Qatar.

The kicker — hiring broker Maribel Equio said no placement fees would be collected, only miscellaneous fees such as for medical tests.

Jimmy resigned from his Qatar job in September 2016, going home a few months later to make the arrangements for his new job.

He and other hopefuls — more than 80 of them — were told they would be able to leave by August this year. First, they needed new medical tests, costing around P4,200 ($84), because the ones they took in Qatar were no longer valid, Equio said.

By this time, Jimmy’s severance pay and savings were starting to dry up. His wife told him to just go back to Qatar but he insisted that a job in New Zealand would be better for the family. Marital difficulties marked the next months for the couple.

But Equio assured Jimmy he would be leaving soon because drivers were in demand in New Zealand. In the meantime, she offered to hire him as her assistant and a shuttle driver for applicants scheduled to leave. He was promised a salary of P70,000 ($1,400).

But in the two months he worked for her, Jimmy never received compensation.

Jimmy’s two brothers were also among the group hoping to work in New Zealand. In a reversal of her earlier promise of no placement fees, Equio now told them whoever could cough up P50,000 ($1,000) would be prioritized to leave.

Although surprised by this, Jimmy’s brothers made partial payments, hoping to leave as soon as possible. They gave Equio a total of P55,000 ($1,100). Other applicants, equally desperate to leave the country, borrowed money from various sources to meet the new requirement.

When the departure date arrived, those supposedly scheduled to leave were brought to the airport for their flight. To their chagrin, there was no flight ticket waiting for them. Neither was Equio.

Jimmy, whose brothers were in the group, had no choice but to assist them, even buying them food.

What they did not know was that Equio had been arrested in an entrapment operation in July. When they did find out, Jimmy and the other applicants went to the National Bureau of Investigation where Equio was detained.

There, she maintained that the workers were already scheduled to leave for New Zealand. She just needed to get out of jail to take care of things.

Again, they believed her and, after a few days, Jimmy and a few of the other applicants gave Equio the P250,000 they had managed to borrow and scrounge for her bail.

And again, they arrived at the airport to find their hopes shattered. Since then, they have not seen Equio.

Today, Jimmy is unemployed. His wife left him when hard times fell on the family. His eldest child had to stop schooling.

2 million OFWs every year

Some 6,000 Filipinos a day — more than 2 million a year — leave the country for jobs abroad, according to the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA). According to the Philippine Statistics Authority estimated the number of overseas Filipino workers who worked abroad at any time between April to September last year at 2.2 million.

To this day, the country continues to rely on overseas remittances to keep the economy afloat. In 2016, Filipinos living or working abroad sent home a record-high $26.9 billion, according to the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas.

Labor export: a Marcos legacy

The early 1970s, under the government of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, the country saw the first major deployment of young Filipino men to the Middle East in response to the region’s increasing need for manpower for the booming oil industry. It was also an opportunity to curb unemployment rates in the country, in light of the idle economy. The policy established a systematic deployment of workers in countries where there is a shortage of labor and wages are higher.

The Middle East continues to be the leading destination of OFWs today.

To facilitate the export of labor, the government established a system of public-private partnership. Government created the POEA with the task of generating and preserving decent employment for OFWs, and to regulate recruitment agencies. Private entities then created recruitment agencies in response to the growing need for labor in foreign markets.

Institutionalizing private recruitment: the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995

In 1995, amid the public outcry over the execution of domestic worker Flor Contemplacion in Singapore, the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act (RA 8042) was enacted. It was the first law to significantly evaluate the government’s labor export policy.

The law aimed to promote the welfare and rights of migrant workers and recognize their significant contribution to the nation’s economy.

It was through this act that the recruitment of workers by government agencies was phased out, with the task completely given over to the private sector.

‘Recruitment is big business’

Filipinos seeking overseas work need to do so through recruitment agencies.

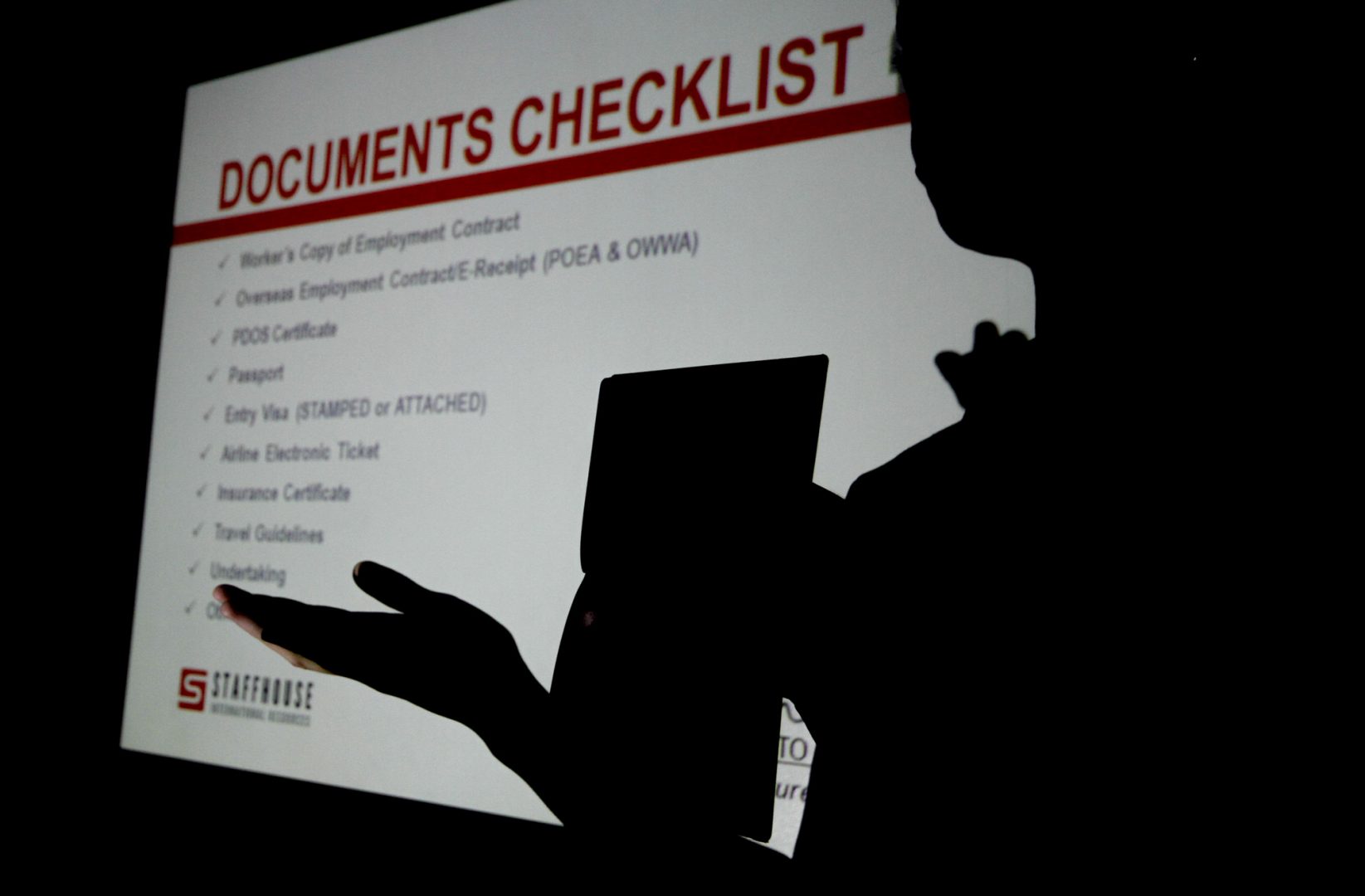

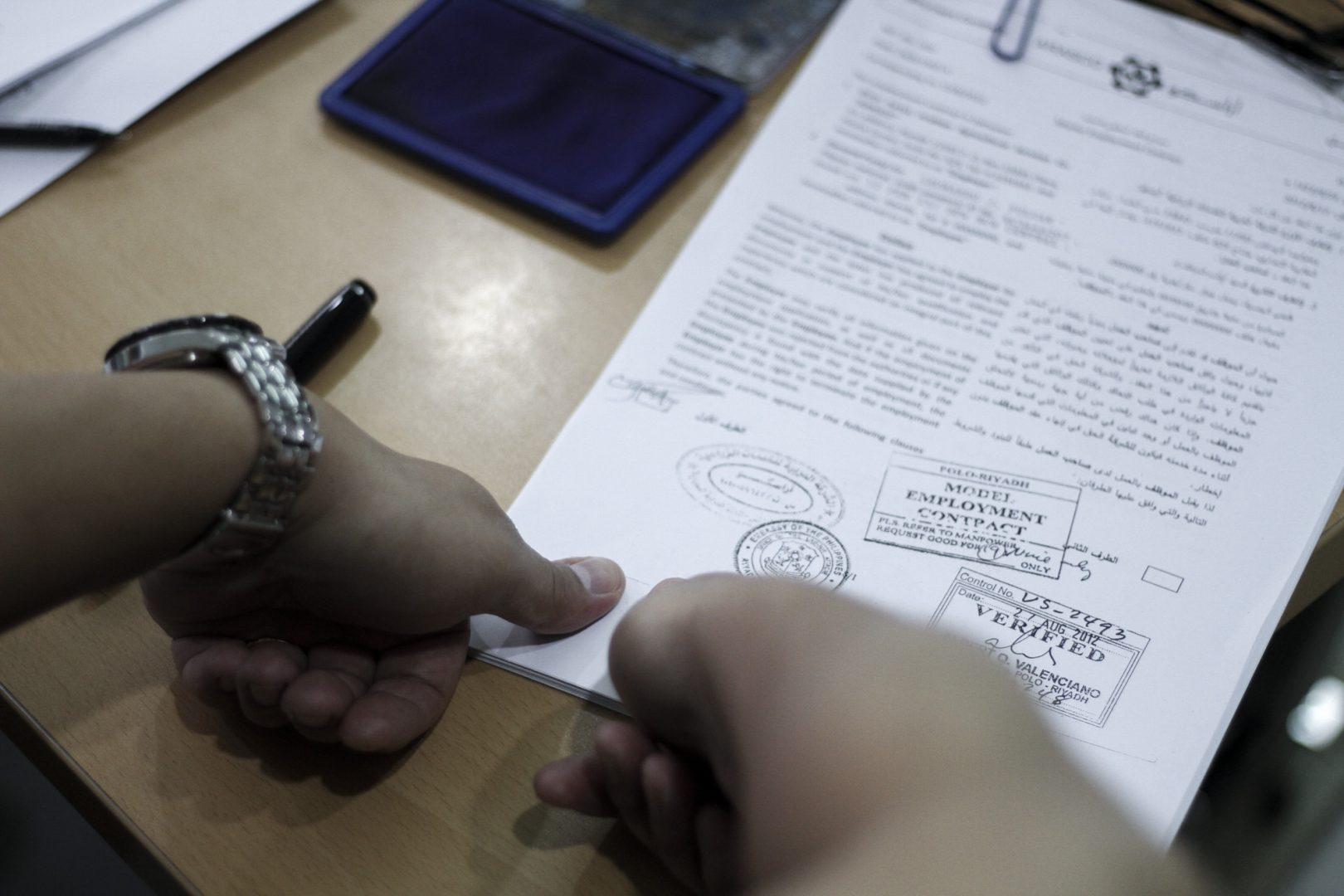

These agencies usually advertise job opportunities and hold recruitment fairs in accordance to POEA regulations. Once applicants are hired by foreign companies, the agencies assist them procure and submit the necessary documents for employment.

Direct hiring by companies is also allowed, in which case workers are responsible for completing their requirements, often subjected to a tangle of government red tape.

Recruitment agencies typically charge applicants placement or recruitment fees for their services. These fees can run up to several thousand pesos, forcing many jobseekers to empty their savings or take out huge loans. And then there is the time and money they have to spend while processing their applications.

“Recruitment is big business in the Philippines,” says Public Services Labor Confederation (PSLink) advocacy head Jillian Roque.

Recruitment agencies are given the leeway to charge applicants certain fees with certain conditions. Under POEA regulations, an agency may only charge a placement fee not exceeding a month’s basic salary.

The Household Service Workers Policy Reform Package

The household service industry, however, is one industry where placement fees have been banned.

Domestic workers, whose poor working conditions were highlighted when the 2006 conflict in Lebanon exposed the risks they faced, spurred the POEA to craft the Household Service Workers Policy Reform Package, with the aim of professionalizing domestic work by setting the minimum age of household workers at 23; requiring a certificate of professional skills training through the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority; pegging the minimum wage at $400; and obliging employers to shoulder the costs of deployment, including placement fees.

However, in a 2011 study, the Center for Migrant Advocacy found that there has been no strict implementation of the POEA directive. Of the 281 workers surveyed, half of them said that they made only an average of $251 a month, well below the required $400.

Roque adds that while the HSW reform package was instrumental in advocating for the rights of household workers, recruitment agencies still managed to find loopholes in the policy. For example, while recruitment agencies may not overtly charge placement fees from domestic workers, but they can charge them for other services such as training fees conducted outside of TESDA. These fees can run up to P90,000, Roque says.

Some agencies also include provisions in their contracts that the first month’s salary goes to them, she adds.

“People are desperate to work abroad, that’s why despite the steep price, they will pay,” Roque adds.

Seafarers are also exempt from paying placement fees, and countries such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada and New Zealand prohibit the charging of such fees.

It remains to be seen if a similar policy shift to eradicate placement fees will be enacted by the government on the recruitment and deployment of migrant workers, in general. But weak implementation of laws and regulations compounds the risks migrant workers face during the recruitment process.

ILO convention 181: Banning placement fees

In 1997, the Philippines signed the ILO convention 181 — Private Employment Agencies Convention — which presented a balanced regulatory framework for private employment agencies. It sought to protect workers from abuse and promote a better relationship between the government and private recruitment firms. Among the provisions in the treaty is banning placement fees.

As of 2013, 27countries had ratified the treaty including Italy, Japan and Zambia — which effectively set legislation that would adopt ILO standards for the regulation of private employment agencies.

The Philippines is yet to ratify the convention.

Protecting workers’ rights: the Fair Recruitment Initiative

The ILO launched the Fair Recruitment Initiative in 2014, in response to growing concerns of human trafficking and migrant workers falling victim to unscrupulous recruiters who charge exorbitant amounts to find employment opportunities abroad. It is a multi-stakeholder initiative implemented in close collaboration with governments, representatives of employers’ and workers’ organizations, the private sector, and other key partners.

The UN agency defines fair recruitment as the right of a worker to seek employment without being burdened by recruitment or placement fees, and the right to be treated with transparency and dignity during the recruitment process. It breaks the common assumption that being able to work abroad is a privilege that can only be obtained by paying obscenely excessive fees, often trapping workers into a cycle of forced labor to pay off debts.

Ethical recruitment as a sustainable business model

“We were deadset on doing things right,” says Marc Capistrano, managing partner of Staffhouse International Resources, an agency that doesn’t charge any fees.

In 1999, Capistrano, who had worked for a corporation, decided to set up a recruitment agency with his friend. As he was by then already exposed to international business practices, he knew that charging fees from migrant workers was unethical. Instead, they devised a business model that would require prospective employers to shoulder all fees related to the deployment of migrant workers.

Capistrano admits they are more expensive than other recruitment agencies. In the beginning, he said, companies were hesitant to enlist their services since they cost more. But for Capistrano, their selling point is their ability to recruit the best candidates.

Staffhouse International currently fields laborers, production helpers, farmers, medical professionals, machine operators and banking and finance managers. Their largest market is Saudi Arabia, where automotive and oil companies demand more laborers.

Over the years, Capistrano says his company has built a reputation for sending the best workers and professionals into foreign markets. The workers they send, he says, also have the reputation of being not only highly skilled but also reliable.

European companies, he says, particularly those from Germany, have sought them out due to their ethical recruitment policy.

He admits that sometimes there are applicants who are wary when they say they do not charge any fees. “They sometimes think we are an illegal recruiter,” he says. But owing to their professionalism and their promise to not charge any fees, he says they are able to attract the best workers.

“All employers are cost-sensitive when they look at our recruitment fees. But we are in a good place [to charge employers] because of our record,” he says.

Regulating the recruitment agency industry

PSLink’s Roque admits that much still needs to be done in terms of promoting fair recruitment.

There needs to be an intensive awareness campaigns on the part of the POEA, she says. Most applicants are barely aware of their rights as migrant workers let alone the fees that can be legally charged by recruitment agencies, making them more at risk of falling prey to dubious recruiters.

While legislation would be a welcome development in terms of eradicating placement fees in the recruitment process, Roque says this might be a farfetched idea, considering the lobbying prowess of these agencies. Instead, she suggests government can at least increase the budget of the POEA to for it to be able to more effectively regulate recruitment agencies.

Capistrano believes that ethical and fair recruitment is a sustainable business model, but recognizes the limitations of influencing other agencies to follow suit.

While there are also other non-fee charging recruitment agencies such as The Fair Hiring Initiative, the standard practice of most agencies remains to charge workers. The challenge, Capistrano believes, is to shift the expenses incurred during recruitment and deployment to the employers instead of the migrant worker.

In a December 2009 forum organized by the Institute of Labor Studies of the Department of Labor and Employment, recruitment agencies lamented that the “no placement fee policy” included in the HSW reform package meant a loss of competitive edge and income for the industry.

If the government would like to see more ethical recruiters, Capistrano believes it can offer more incentives to fair recruiters, by lessening, for example, the red tape in processing contracts. Solving the problem of lengthy processing times and multiple document requirements could also curb the appeal of illegal recruiters who promise speedy processing of applications.

Seeking ethical recruiters

Leonardo Fulgar, 40, recently returned to Saudi Arabia as a technical superintendent in August 2017. A father of three children, he says seeking employment abroad was a necessary decision for his family. He dreams, though, of going home permanently in ten years.

“I need to pay for the lot that I bought for my family, then I would like to start a business,” he says.

He says being employed abroad has its ups and downs. As a professional, he says he has learned so much from his co-workers and from his employers, but once in a while he is still struck with homesickness.

He enlisted the services of Staffhouse International to facilitate his application. He has been an OFW for nine years and paid a placement fee of P23,000 ($460) in his past deployments to Doha, Qatar, through a different recruitment agency.

Fulgar says he intentionally sought a recruitment agency that did not charge a placement fee because he did not see its necessity.

Unfortunately, for many other migrant workers, recruitment fees are still seen as a requirement to be able to work abroad.

‘It’s possible’

Jimmy, the driver from Bacolod City, is currently applying to be a driver and caretaker in Israel. He is also among a group of migrant workers pursuing a case against Equio, who swindled more than 80 applicants of millions of pesos.

When asked if his current agency charged him a placement fee, he says it thankfully did not.

“Puwede naman po pala iyon (na walang recruitment fee). Sana ganoon din dati (So it’s possible to find work without paying recruitment fees. I wish that happened in the past).”