Late every afternoon, after a tiring day at school, Arabic language teacher Salema Haji-Ekshan would retreat to the small garden of her house in Barangay Ambulong in Marawi City to make time for herself, tending her vegetable patch and, always the highlight, gazing at her prized orchids.

With the cool Marawi breezes working their calming magic, Salema said, “for a moment, I (would) forget my problems.”

But that was then.

Since May 23, when she and her two daughters had to flee when fighting erupted between government security forces and extremist gunmen, she has not had the chance to forget the problems facing her.

Gunmen of the Maute group told them to leave so they would not be caught in the crossfire. The only thing they managed to bring aside from the clothes they wore were Salema’s kumbong, or hijab, and the schoolbags of her daughters, who had just returned from school.

Salema and her daughters now stay in an informal evacuation center, an unfinished house in Bara-as, Iligan City owned by a distant relative living abroad, which they share with 25 other families.

“Nami-miss ko na ang bahay ko sa Marawi. Kahit kubo lang ‘yun, sa akin. Nami-miss ko lalo ang garden ko. (I miss my house in Marawi. Even if it was just a hut, it was mine. I miss my garden most of all),” she says. Before they left, daisies were already blooming, her daughter Marjana adds.

200,000 displaced

More than 200,000 Marawi residents have been displaced by the continuing fighting, which continues to rage after more than four months, despite several deadlines announced by the government.

Many more are unaccounted for, although the Department of Social Welfare and Development surmises hopefully that most of these managed to flee and have sought refuge with relatives.

More than a month after government forces captured Marawi’s Grand Mosque, the fighting has not eased. And yet, despite several missed deadlines, the military — and President Rodrigo Duterte — continue to predict when the crisis will end.

Recently, the military said they would be able to wipe out or drive out the extremists by October 15, even as they acknowledged that there may be more hostages in the gunmen’s hands than they thought.

And Duterte, speaking to Australian sailors on the visiting HMAS Adelaide on Tuesday, expressed hopes of ending the fighting within a week.

‘Our house title was not a priority’

In their haste to escape harm, many refugees Marawi took nothing with them when they fled. Most thought the shots that signaled the outbreak of fighting were another rido, a clan feud Marawi residents say would often erupt but would not last beyond three days.

Salema says she was pregnant with her first daughter Marjana when she and her husband bought their house from money he saved as a gold trader. Her husband died in 2008 from a stroke.

When she fled, she left behind the title to the house and her government-issued IDs. “Hindi na namin priority ang titulo noong may giyera na. (The title of our house was not a priority when the war erupted),” she says.

Now, Salema fears, without proof of ownership she might not be able to reclaim her home when she returns.

‘Marawi is ours’

Mariam Sultan, 52, owned a small business with her husband, a mechanic. She shares Salema’s fear.

Because her priority was taking her daughter Sittie-Naura, then eight months pregnant, to safety, she wasn’t able to bring any important documents.

She now lives in a toril — a live-in school for Muslim children — in Barangay Obaldo Laya, Iligan City that has been turned into an evacuation center. With only donations to rely on for their needs, she says hard is an understatement.

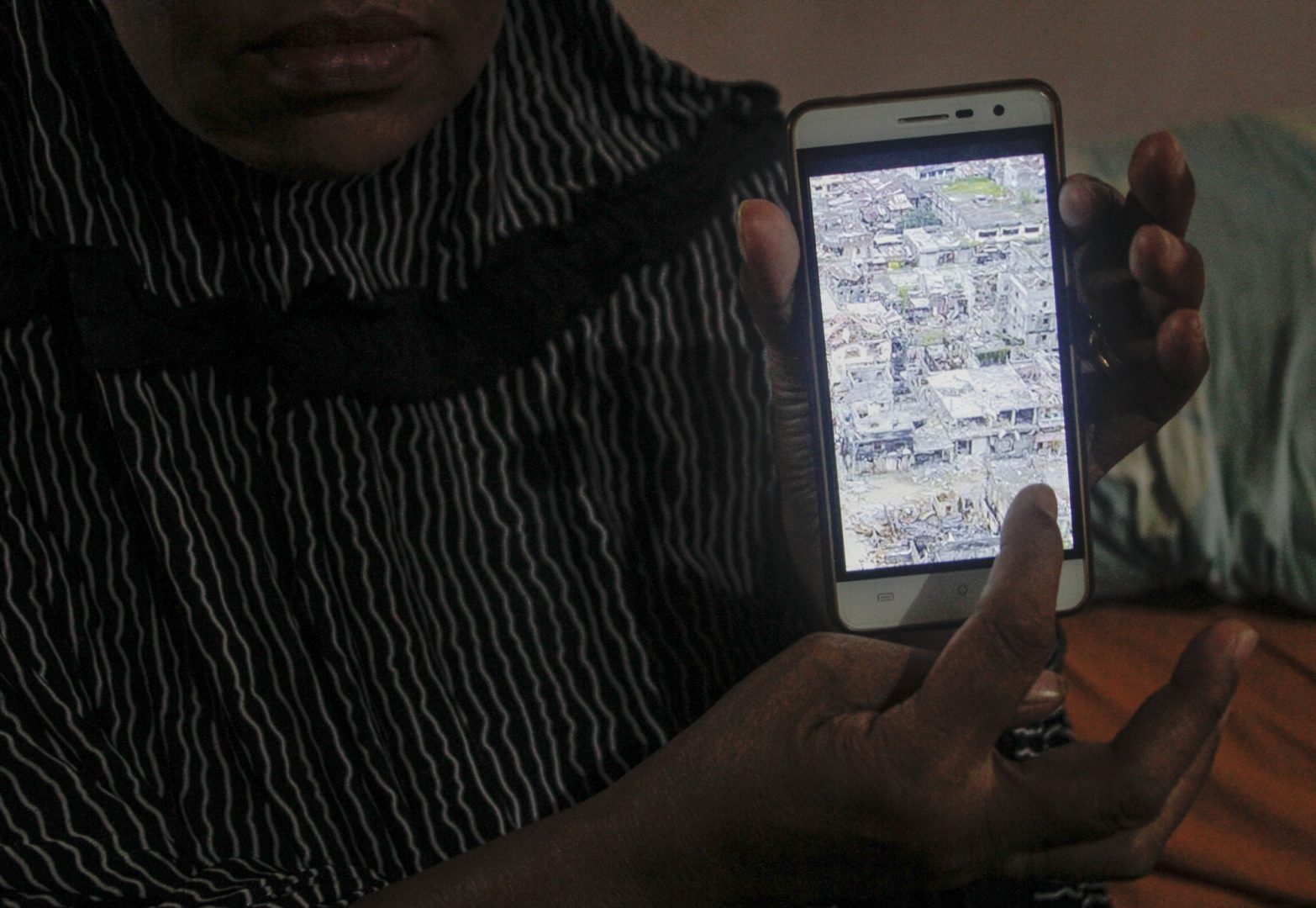

Her heart breaks whenever she sees photos of what the fighting has done to Marawi.

Recently, she saw an aerial photo of the city and recognized a building. Showing the photo, she tearfully points to her three-story house, which bombs have destroyed.

“Gusto kong makabalik sa Marawi. Kahit asin lang ang kainin namin du’n, sa amin ‘yun. Iba pa rin sa sarili mong lugar. (I want to go back to Marawi even if all we eat there is salt. That is our home),” she says.

Rebuilding: the pivotal challenge

Rebuilding Marawi will be the pivotal challenge for Duterte — the first president from Mindanao and who claims a Maranao bloodline.

The government estimates P50 billion will be needed to reconstruct and rehabilitate Marawi.

In July, Duterte ordered the creation of the inter-agency Task Force Bangon Marawi to be headed by Defense secretary Delfin Lorenzana and Public Works and Highways Secretary Mark Villar.

Lorenzana, the head of the task force and the administrator of martial law, which Duterte declared over Mindanao, has instructions to prioritize rebuilding damaged homes and infrastructure.

He needs to do it right or risk dissatisfaction that could spark another wave of radicalization.

‘Marawi is the land of our forefathers’

Recently, Salema bought a pack of chalk. She says she misses teaching and worries that the refugee children are unlearning their Arabic lessons. It is important for the children to learn Arabic, she says.

In the afternoon she uses one of the walls of the unfinished house to teach basic Arabic.

Salema hopes she will be able to go home soon to Marawi — the land of her elders, the place of her birth, her children’s home.

Although hopeful, she worries she might not be able to go back to the house she and her husband built.

“Puwede ba kaming hindi makabalik sa bahay namin? Doon kami pinanganak, sa amin iyon. Saan kami titira? Lugar namin iyon. Mula pa sa mga lolo at lola namin ‘yung lupain. Sino’ng kukuha sa mga lugar namin? (Is it possible that we won’t be able to go back home? We were born in Marawi City. The land where my house was built was owned by my forefathers. It is ours. Where will we live? Who will take our land?),”she says.

Iligan City, much as it has provided sanctuary, is not home.

“It is not ours, Marawi is ours,” Salema says.