SHANGHAI/PARIS — When China unveiled an historic order for its first large commercial jetliner at a national air show in 2010, Western journalists were kept away, and only local media were allowed to witness a major turning point in China’s aviation ambitions.

The COMAC C919 jet is expected to stage its maiden flight in the coming weeks, and foreign media and potential buyers will be invited in force — illustrating how Beijing is adjusting to competition for a slice of global jet sales worth $2 trillion over the next 20 years.

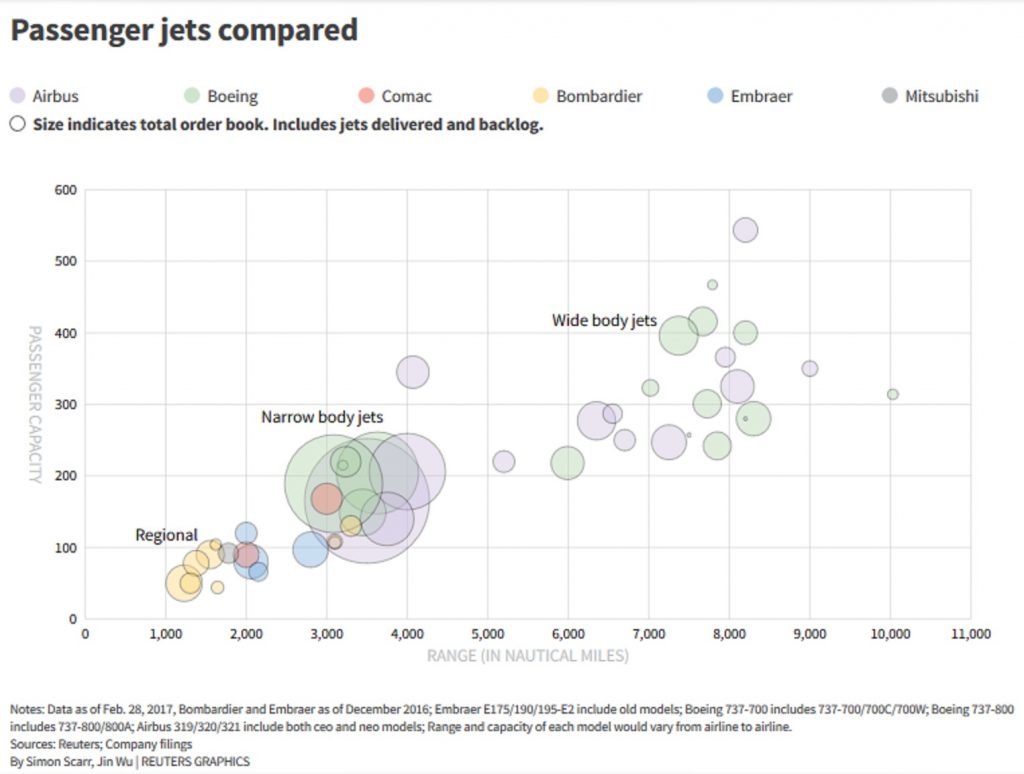

But after three years of delays and almost a decade in development, China’s answer to the Boeing 737 and its state-owned designers face a daunting phase: selling the jet abroad in a market dominated by Boeing and Airbus.

“They will be trying to compete on price against people who are building aircraft at a much faster pace and with more experience, so there’s a risk of getting bled dry,” said Richard Aboulafia, aerospace analyst at Virginia-based Teal Group.

Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China has some cards to play: its plane has Western engines and avionics coupled with a new design; it’s rolling out a pilot training program, expanding international staff and has strong, behind-the-scenes backing from Beijing, industry executives say.

And though still unproven, COMAC could be the single biggest threat over the coming decades to the dominance of Boeing and Airbus, both in China’s own huge aviation market and, longer-term, overseas. The C919 is the first step to this.

Beijing’s backing for the single-aisle plane gives COMAC a springboard in the world’s fastest-growing domestic market, even though the company acknowledges much bigger hurdles abroad.

“You can’t compare us to Boeing or Airbus, they’re in a different strategic stage… We took half a century to solve the first strategic issue (of plane development), it will also take many years to solve the second (market) problem,” said Jeff Cheng, a spokesman for COMAC. “After the first flight, we have to focus and research on how to improve the plane’s and COMAC’s market competitiveness.”

Eric Chen, president of Airbus Commercial Aircraft China, welcomed the competition from COMAC, and a China-based spokesman for Boeing congratulated the company on developing the C919.

Global support network

The C919 has chalked up 570 firm orders and commitments from 23 customers, mainly Chinese state-backed airlines and leasing companies, but says it is not able to give a breakdown.

In comparison, the latest version of the Boeing 737 had more than 3,000 firm orders before it flew last January.

Those types of numbers from the two big global plane makers come after decades of trimming costs and honing marketing pitches. The two have global support networks able to respond whenever a jet breaks down just about anywhere, and the number of jets flying makes it easier for airlines to raise loans to buy them.

While Chinese financiers have muscled into the global aviation arena, COMAC has a relatively low-key presence at international air shows and has said the C919 will initially be aimed at the domestic market. But there are signs it’s adopting a more outward-facing approach.

While operating manuals for COMAC’s smaller ARJ21 regional jet, which took its first flight in 2007, were written in Mandarin, the C919’s will be in English to support sales.

COMAC’s sales and support networks — it has at least 50 people in its sales and marketing departments, says Cheng — are, however, a fraction of those at Boeing and Airbus.

Still, COMAC’s home advantage is significant as Chinese airlines are likely to drive airplane demand over the next two decades, buying nearly 7,000 planes — mostly from Boeing and Airbus.

“Their sales person is the government,” said a Chinese airline executive, who didn’t want to be named for risk of damaging business relationships. “As long as the government tells the state airlines to purchase planes, that will happen.”

Airline executives say the first flight is when COMAC can realistically start discussing deposits and firming up customers, even if the plane still faces years of testing.

“We haven’t placed a deposit; at the moment, it’s intentions,” said Che Shanglun, chairman of Xiamen Airlines, a subsidiary of China Southern Airlines, which has committed to buying up to 50 of the 158-seat C919s.

“We signed for 50, but we actually want to buy 30. We have to see if they’re able to produce it … They (COMAC) are very enthusiastic, they meet us every month and send us updates.”

How safe is it?

Executives at two Chinese airlines which have not placed orders for the aircraft said they wanted to see the C919’s safety record, as well as the creation of a global support team.

The safety certification of the new plane — which state media says will have a catalog price tag of around $50 million, less than half that of a Boeing 737 or Airbus A320 — could be among the biggest issues for the C919 internationally.

Having a plane certified to fly commercially is tough enough even for Western jet makers as aircraft become more complex and supply chains expand. There is still uncertainty over approvals needed for the C919 to secure a foothold beyond China, with the United States and European Union having the most influence.

Although the EU has agreed to recognize some of the checks carried out by China, it is expected to insist on some of its own tests before issuing a safety certificate and is trying to understand where discrepancies between the two systems lie.

“We are just at the start of the process,” said Patrick Ky, executive director of the European Aviation Safety Agency.

The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Without Western approvals, China would only be able to sell to countries that accept its certification standards. Zimbabwe, Bolivia and Tajikistan have previously bought Chinese planes.

Without Western certification, “sales of the aircraft in developed economies and many developing economies will be difficult to impossible,” said Bradley Perrett, a veteran China watcher at Aviation Week.

The C919’s only real foreign buyer so far is leasing firm GE Capital Aviation Services, whose parent General Electric co-built the plane’s engine with France’s Safran.

“Only once our plane enters the market and is tested can we see what gaps it has,” Cheng said.